-

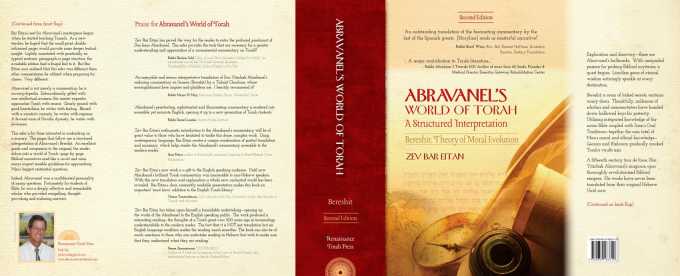

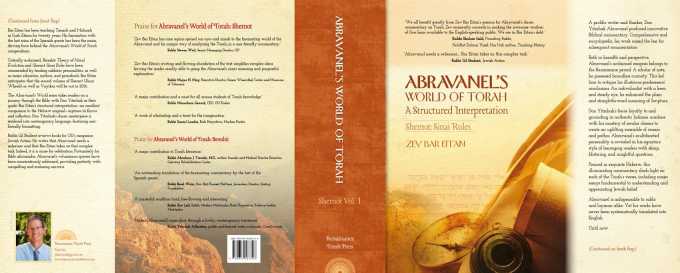

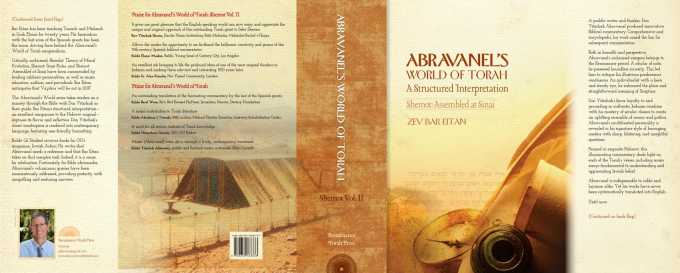

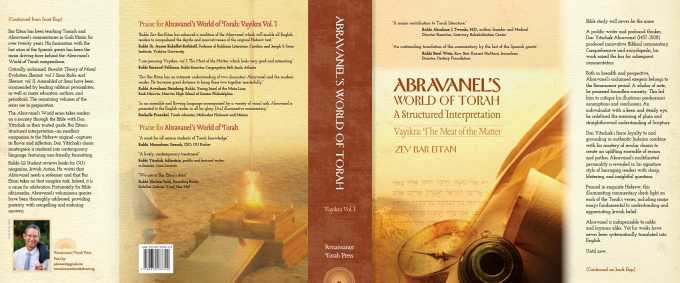

Abravanel’s World of Torah

is an enticingly innovative yet thoroughly loyal rendition of a major fifteenth-century Hebrew classic.

For the first time, Don Yitzchak Abravanel’s Bible commentary has become accessible IN ENGLISH.

Abravanel’s World of Torah: Series

Bible studies

-

Bible Studies: Jacob at the Well

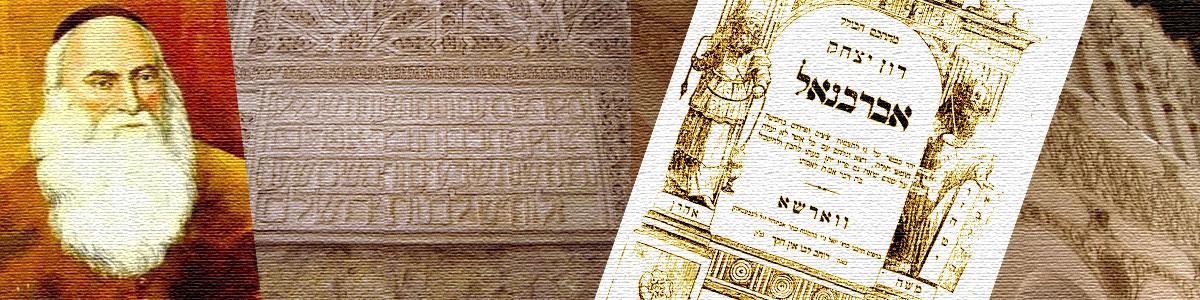

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 29, Jacob arrives at a well, outside of Haran. There, in a setting

teeming with rich imagery, he meets local shepherds and plies them with questions. Abravanel explains

the significance of the dialogue at the well, both significant topics for Bible students. As to Jacob’s

questions, what was he getting at? Here is Abravanel’s interpretation.“Then Jacob went on his journey, and came to the land of the children of

the east…And he looked, and behold a well in the field…And Jacob said

unto them, My brethren, from where are you? And they said, We are

from Haran. And he said unto them, Do you know Laban the son of

Nahor? And they said, We know him…And he said unto them, Is it well

with him? And they said, It is well. And behold, Rachel his daughter

comes with the sheep.”Jacob sought out Laban, Rebekah’s brother, this despite Isaac’s advice. The aged patriarch had called for

Jacob to pay a visit to Betuel, Rebekah’s and Laban’s father. First, Jacob learns from the locals that he

arrived in Haran. Next, Jacob asks: “Do you know Laban the son of Nahor?” Yet, Laban was the son of

Betuel and grandson of Nahor.Abravanel clarifies. Of course, Jacob knew Laban’s lineage. The reason he calls Laban the son of Nahor

(and not Betuel) was Jacob’s way of paying respect to the family’s pedigree. Nahor was Abraham’s

uncle. Pegging Laban to Nahor underscored the more prestigious family ancestry.Next, Jacob asks: “Is it well with him?” Abravanel understands the question, not as a nicety, but rather

as a crucial barometer. Jacob needed to know if Laban lived in peace. The patriarch feared that perhaps

a tribal feud engulfed Laban and the townspeople. Jacob had plenty of infighting back home. He needed

a breather.No sooner had Jacob heard that peace reigned in Haran than more favorable news followed. “And they

said, It is well. And behold, Rachel his daughter comes with the sheep.” When Jacob heard about good

neighborly relations in Haran, followed by news that Rachel was approaching, a strong premonition

from Above overcame him – he felt certain that the two were destined to marry.How did Jacob know that Rachel would be his bride? He had heard the story of divine providence, one

that arranged for Rebekah to meet Eliezer, Abraham’s servant, at the well. The venue turned out to be a

precursor, as Isaac and Rebekah married. Now, Jacob felt that the well, with its history and symbolism

alluding to life, would become the backdrop whereby he would find his wife.In sum, Abravanel argues that Jacob’s arrival at the well, and the conversation with Haran’s shepherds

that took place there, was anything but casual or chance. It had the mark of divine providence written

all over it. -

Bible Studies: Jacob Becomes Israel

In Blble studies, Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 35, we read that Jacob and family edge closer to home, to Isaac in

Hebron. Along the way from Paddan-Aram, God appears to the patriarch and confirms what an angelic

messenger had told him earlier – a name change was in the offing: “Your name shall not be called any

more Jacob, but Israel shall be your name.”“And God appeared unto Jacob again, when he came from Paddan-

Aram, and blessed him. And God said unto him, Your name is Jacob.

Your name shall not be called any more Jacob, but Israel shall be your

name. And He called his name Israel.”Abravanel contrasts Jacob’s name change to Israel versus Abram’s becoming Abraham – really a world

of difference. Let’s start with the operative verse for Abraham: “Neither shall your name any more be

called Abram, but your name shall be Abraham…”Abravanel teaches that whoever refers to Abraham by his original name contravenes divine will. This is

because the Creator completely uprooted and rescinded the first patriarch’s birth name. The same

applies to Sarah’s name change from Sarai.Jacob’s change to Israel, Abravanel learns, needs to be understood in a different light; it’s a revision.

Importantly, the appellation given to the third patriarch by his father Isaac was not voided. Here’s the

thinking.Abram’s and Sarai’s names changed as a direct result of entering God’s covenant, at the time of

Abraham’s circumcision. Consequently, it fit to erase both of their originally given names, as they

received them in a wholly non-kosher and morally defiled milieu. The moment that Abraham and Sarah

entered into the divine covenant, they received a spiritual boon. Thus, those early names, tainted by

pagan culture, fell by the wayside forever.Jacob’s circumstances were night and day from Abraham’s and Sarah’s. Isaac had designated Jacob’s

name when he ushered his son into the Abrahamic covenant. That appellation resonated with holiness

and divine inspiration. Hence, it would be wrong to uproot that sacred appellation and have Israel

supplant it, even though Heaven’s angel called Jacob by the name of Israel, for good reason. “Your name

shall be called no more Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and men, and have prevailed.”To conclude, the name Israel complements and supplements Jacob, but does not replace it. Here’s a

caveat. Israel should be viewed as the primary name, Jacob the secondary one. This hierarchy reflects

the givers’ respective identities. Since a divine angel renamed the patriarch, that trumps Isaac’s

designation. -

Bible Studies: Jacob Returns Home

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 32, Jacob begins his trek home. The first leg of his journey starts

auspiciously; angels huddle around him.“And Jacob went on his way, and the angels of God met him. And Jacob

said when he saw them, This is God’s camp, and he called the name of

that place Mahanaim. And Jacob sent messengers before him to Esau

his brother…”Abravanel probes Jacob’s mindset, as he parted ways with Laban, a most trying man. “And Jacob went

on his way, and the angels of God met him.”Long years under Laban’s roof and employment had sapped

the patriarch’s strength. Seeing Laban and company shrink into the horizon gladdened Jacob’s heart and

put a bounce in his gait. He breathed a sigh of relief. Unburdened.Invigorated in body and soul, Jacob regained his prior energy level. Elated, he received prophecy, the

same as he had experienced when he left the Holy Land. At that time, he beheld a vision with a ladder.Now Jacob saw something else. “This is God’s camp”, the patriarch declared. Abravanel deciphers the

telling image, explaining that “God’s camp" refers to divine providence – and more. “Camp” carries

military overtones. According to Abravanel, the vision boosted Jacob’s morale. “And he called the name

of that place Mahanaim.”In Hebrew, “Mahanaim” means camps, in plural. Heavenly agents would join

forces with Jacob’s men. Together both camps would rally to defend and protect Jacob and family.Abravanel investigates our verse more thoroughly. “And Jacob went on his way, and the angels of God

met him.”He asks: Who were these angels of God? Were they, as we posited above, the heavenly sort

of beings, relaying the Creator’s message to the patriarch? The problem is, as Abravanel notes, they

didn’t relay anything to him. Furthermore, the verb “met” seems peculiar. Better, the verse should have

said that these angels appeared to Jacob.Abravanel suggests the following. When Jacob bid farewell to Laban, he didn’t know that the road he

chose to take him home was on a collision course with Esau, his brother. Had Jacob known, Abravanel

writes, Jacob would have opted for an alternative route so he could avoid the fraught confrontation.Abravanel provides two distinct approaches in determining the identities of the “angels of God.” One,

the patriarch beheld a divine image. It was of the Maker’s angels converging upon him. They encircled,

giving Jacob a sense of safety. Silently, they surrounded him. No enemy would penetrate God’s lines of

defense. “And Jacob said when he saw them, This is God’s camp.”After Jacob saw the angel’s formation,

he felt less apprehension about the imminent encounter with Esau. Jacob’s side outnumbered Esau’s.Here is Abravanel’s second approach to reveal the identity of the “angels of God.”These angels weren’t,

well, the angelic type. They were merely passersby. As is the wont of travelers, Jacob struck up a

conversation with them. One thing led to another. It came out that these travelers casually mentioned

to Jacob that just down the road, in the direction Jacob was heading, they had seen a band of soldiers.

When Jacob questioned his new friends further, he ascertained that the warriors were none other than

Esau and his men. For Jacob, the “casual” meeting with these travelers proved invaluable and timely.

And as we shall see later in this chapter, Jacob will prepare himself accordingly. For the religiously-

attuned patriarch, these travelers were indeed angelic. -

Bible Studies: Jacob's Ladder

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 28, Jacob leaves home and makes his way to Haran. The patriarch

rests along the road. A prescient encounter with God will change his life forever. Abravanel deciphers

the prophecy – Jacob’s ladder.“And Jacob went out from Beer-Sheba, and went toward Haran. And he

lighted upon the place, and tarried there all night…And he dreamed, and

behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven.

And behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it.”For elegance and mystique, few Biblical passages surpass the sublime story of Jacob’s ladder. A towering

ladder, a vision that depicted angels in upward and downward movement. Abravanel asks a core

question: What it’s all about? Is God tutoring Jacob in the realm of heaven’s inner workings or

mechanics, as other Bible commentators conclude? If so, why didn’t the Creator reveal the heady stuff

to Abraham and Isaac when He communicated with them?Continuing, Abravanel wonders about the timing of the dream. Why did the Almighty convey esoterica

to Jacob now, when he was spent and road weary, en route to distant Haran? Far better, Abravanel

proposes, had God apprised Jacob of these intricate laws of the universe while he learned with his

father Isaac, or in the ancient study halls of Shem and Eber. Jacob in either of those academic settings

felt calm, and had the right frame of mind to receive Heaven’s tutorial. Lastly, Abravanel asks about

context. How is the vision connected to the overall narrative, given the backdrop of the circumstances

that prompted the patriarch’s exit from Beer-Sheba?Abravanel lists his predecessors’ approaches, and there are many. Here we only zero in on his. See

Abravanel’s World for the full discussion. By way of preface, Abravanel challenges Bible students to

evaluate all the approaches, including his own, to determine for themselves which one rates as the most

logical and reasonable.Indeed, context matters. For that reason, Abravanel says, God appeared now to Jacob and not at other

earlier junctures in the patriarch’s lifetime. Further, the vision of the ladder came to Jacob and not

Abraham or Isaac, in a communiqué tailor-made for him.In a word, God sought to comfort Jacob’s brooding mood, patch his wounded soul. Jacob had just duped

his blind father. Further, Jacob infuriated Esau, to the point where the patriarch feared for his life at his

brother’s hand. Penniless, a destitute and lonely Jacob fled.Nagging doubts gave Jacob no respite. Regret consumed him. Had God disapproved? Had the Maker

resolved to soundly punish him for unconscionable conduct toward Esau? Was stealing the blessing

worth the risk of death? Was exile from the Holy Land the Creator’s punishment to a crestfallen

patriarch, the first of endless wanderings?Indeed, self-doubt haunted Jacob. Still, that night he slept, “and he dreamed, and behold a ladder…”

Abravanel illustrates how God’s uplifting dream reassured Jacob; he need not worry. He informed Jacob

that his father’s blessings reached the right son. “And behold God stood beside him and said, I am

God…The land whereupon you lie, to you I will give it, and to your seed. And your seed shall be as the

dust of the earth.” Jacob heard that Heaven approved of his actions. “And behold I am with you.” As for

Esau’s intent to kill Jacob, his evil plan will be thwarted, “and will keep you wherever you go…”In short, Jacob’s vision apprised him of beautiful blessings in store, including heavenly protection via

divine providence. -

Bible Studies: Noah the Righteous

“These are the generations of Noah. Noah was in his generations a man

righteous and whole-hearted. Noah walked with God.”Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. In Genesis chapter 6, the Bible focuses on an exemplary personality: Noah.In glowing terms, the Bible extols Noah as righteous and whole-hearted. Abravanel takes a deeper dive

into this survivor’s stout soul, showing ways in which Noah exceled in an era when a world tottered and

tanked. Indeed, as Noah’s neighbors corrupted their ways and wallowed in morass, “Noah walked with

God.”Abravanel quotes a rabbinic epigram that best contrasts the values of virtuous Noah from his

unscrupulous contemporaries. The translation of the witticism goes like this: While mankind gorged

their bodies and starved their souls, Noah nourished his soul, and starved his body.In what ways did Noah please his Maker? “Righteous” refers to Noah’s interpersonal relationships. With

his fellow man, Noah was honest. He took pains to treat each person fairly, courteously. This is in

marked contrast with those around him. The generation was more than inconsiderate to others; they

were mean-spirited and deceitful.There was a second aspect that distinguished Noah from his contemporaries. Decency defined him.

His attitude toward the physical world and its pleasures came without misplaced hype. Noah

displayed steely self-discipline to material things. As for the rest of the planet, moderation was not in

their lexicon. Nor was fair play.Whim ruled. Bigtime. Gluttony proved their undoing. Man and animal alike acted out unnaturally in

pursuit of perversion.Abravanel adds something else about Noah. Despite a dystopian culture of sin, Noah stood apart. For

him, crisp demarcation lines divided right from wrong. Smut held no sway over him, let alone blur God’s

ethos. From youth until old age, Noah’s swerved not an iota from divine service. Through hell and high

water, “Noah walked with God.” Literally.Readers will find that Abravanel details, and heaps, more praise for Noah in Abravanel’s World.

However, before concluding this blog, let us share one aspect of Heaven’s favor and divine providence

for loyal Noah, as per Abravanel’s understanding.Genesis’ first chapters record a meteoric population growth trajectory, with early man begetting and

begetting and begetting. Yet, Noah’s family was, to be colloquial, nuclear in size. He fathered only three

sons. Abravanel learns that, typically, a father of many children cannot fully devote himself to his kids’

education. Had Noah’s family waxed many, undoubtedly, some of the sons would have been influenced

by a wayward world. However, because Noah’s number of children was small, he kept a keen eye out for

creeping unacceptable attitudes and behavior. A vigil dad will nip trouble in the bud.Abravanel says more. He understands that Noah did not father daughters. Had he, then, perforce the

daughters would have married men – all rotten to the core. Noah’s grandchildren would have followed

the despicable ways of their fathers. As a case in point, Abravanel brings an example from Lot’s

daughters. When Sodom and Gomorrah fell to fire and brimstone, so too did Lot’s married daughters.Based on Abravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan

-

Bible Studies: The Jews and Divine Covenant

“And Moses wrote all the words of God, and rose up early in the

morning, and built an altar under the mountain, and twelve pillars for the

twelve tribes of Israel.”Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. To provide backdrop, when we get to Exodus chapter 24, the Hebrews have already

heard the Ten Commandments directly from God. The ultra-intense experience left the people

overwhelmed, and petrified. In efforts to regain their equilibrium, they distanced themselves from the

base of the mountain. In addition, they pleaded with Moses to be their intermediary with the Almighty

so to avoid any more hair-raising encounters with the divine. The Hebrews also pledged that whatever

God asked of them, they would “do and obey.”What happened next, Abravanel asks? That evening, Moses ascended Sinai and relayed the Hebrew’s

stance. God then conveyed a raft of statutes to the prophet. At the crack of the following dawn, Moses

“rose up early in the morning, and built an altar under the mountain, and twelve pillars…” Namely, after

he descended the mountain, he erected an altar of earth at Sinai’s base, beside “twelve pillars for the

twelve tribes of Israel.”Abravanel continues, explaining that at this juncture God and the Jewish people entered into a new

covenant, one sanctified with blood to commemorate the Hebrew’s acceptance of the Torah. “And he

sent the young men of the Children of Israel, who offered burnt offerings, and sacrificed peace offerings

of oxen unto God.” Abravanel posits that the verse speaks of strapping youngsters who could lift the

heavy loads of animal sacrifices, in assisting the encampment. Burnt offerings consisted of sheep. They

were burnt on the altar. Peace offerings, on the other hand, were oxen. People ate and enjoyed the

roasted beef.At this juncture, the Jews entered into a covenant with the divine. “And Moses took half of the blood,

and put it in basins, and half of the blood he dashed against the altar.”Another verse describes how

“Moses took the blood, and sprinkled it on the people, and said: Behold the blood of the covenant

which God has made with you in agreement with all these words.”Abravanel wonders: how did Moses sprinkle blood upon myriads of Jews? He suggests that half of the

blood was flicked upon the main altar, while the other half of blood had been dashed upon the twelve

pillars, each pillar corresponding to distinct Hebrew tribes. In that way, Abravanel teaches, it was as if

blood had been sprinkled upon each Jew.For the full discussion of the covenant, see Abravanel’s World.

-

Bible Studies: The Patriarch and the King

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 14, the Bible chronicles Abram’s dashing military success, which freed

Lot and the other captives who were snatched from their homes in Sodom, and led away.“And the king of Sodom said to Abram: Give me the persons, and take

the goods for yourself. And Abram said to the king of Sodom: I have

lifted up my hand unto God, the God most high, Maker of heaven and

earth, that I will not take a thread nor a shoelace nor anything that is

yours, lest you say: I have made Abram rich, except only that which the

young men have eaten, and the portion of the men who went with me,

Aner, Eshcol, and Mamre. Let them take their portion.”Further, the Bible records a conversation between Abram and the king of Sodom. It turns on the

question of war spoils. The patriarch, out of strong feelings of family ties for his captured nephew Lot,

risked everything to save him. In a daring military raid, under cover of night, Abram and his Canaanite

allies, saved the day. All of the Sodom prisoners, together with that city’s chattel were wrested away

from the enemy. The valorous patriarch was greeted by a jubilant king. Sodom’s royal highness desired

to reward commander Abram handsomely, legitimately so.Abravanel is puzzled by Abram’s refusal to accept the prizes of war, offered by Sodom’s monarch. Fair is

fair. From time immemorial, there have been conventions about these matters. Victorious warriors were entitled

to the lion’s share.Why, Abravanel asks, did the patriarch turn the king down? Abravanel goes further, questioning if the

patriarch exhibited hubris by declining the king. Indeed, Bible students need to understand Abram’s

position. What was he conveying or signaling?Abravanel lays important groundwork into morality. He says that it comes down to honing ethical

excellence; at least one aspect of it: gift giving and gift receiving. In a word, the moral man works within

a well-guarded milieu. He fraternizes with like-minded truth seekers.When the patriarch refused the king’s munificence, he conveyed a not-so-subtle message. That is,

Abram was not interested in befriending the king of Sodom. Why?Sodomites weren’t just licentious, though that would have been enough to turn Abram’s stomach. They

were heartless to the poor and needy, enshrining it in their bylaws and local governance.Of course, the patriarch wanted nothing to do with it, for it was an anathema to his refined inner fiber. A

king of Sodom is still a Sodomite and Avram was discerning when it came to choosing friends.And thus, the patriarch spurned an injudicious alliance with Sodom’s king, stating: “I will not take a

thread nor a shoelace nor anything that is yours…” -

Bible Studies: The Rape of Dinah

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Genesis chapter 34 covers the violent rape of Dinah, and subsequent revenge killings

carried out by her brothers.“And Dinah the daughter of Leah, whom she had borne unto Jacob, went

out to see the daughters of the land. And Shechem the son of Hamor the

Hivite, the prince of the land, saw her. And he took her, and raped her,

and humbled her.”Abravanel provides Bible students his perspective on the crime and punishment. Given that Shechem

son of Hamor committed the rape, was it excessive punishment to massacre all the men of the village,

Abravanel asks? “And it came to pass on the third day…that two sons of Jacob, Simeon and Levi, Dinah’s

brothers, took each man his sword…and slew all the males.”And, if we put forth that Jacob’s sons sought to avenge Dinah, why did they subsequently pillage the

place? “And all their wealth…they took…even all that was in the house.”Abravanel asserts that revenge,

if it is to be morally defensible, must adhere to strict parameters. Certainly, greed cannot enter into the

equation. Thus, after Jacob’s sons killed the men and rescued Dinah, why did they take booty?Abravanel dives into the chapter devoted to Dinah’s rape – and repercussions. He bases the discussion

on the legal/moral code that was widely accepted and practiced by the ancients. We speak of the

Noahide laws. That code, among other things, forbade promiscuity and stealing – on penalty of death.These are Abravanel’s prefatory remarks. In that light, Dinah’s brothers must be judged, Abravanel

posits. Rape, of course, violated the law. Stealing, also, infringed Noahide laws. By raping Dinah, and

then abducting her, Shechem the son of Hamor committed multiple crimes. As for Shechem’s fellow

villagers, they didn’t utter disapproval, let alone criticize the prince’s felonies. Silence in the face of

crime was tantamount to collusion. According to Noahide standards, Shechem’s fellow citizens’ tacit

consent amounted to culpability – punishable by death.Here's more evidence against the townspeople. Shechem and Hamor gathered their countrymen to

discuss the terms by which Jacob and his sons would dwell among them – they were all to undergo

circumcision. “These men are peaceable with us” the princely father and son declared to the assembled.

“Therefore, let them dwell in the land, and trade therein, for behold the land is large enough for them.

Let us take their daughters for wives, and let us give them our daughters.” The referendum, per se,

passed with loud cheers. And all the men underwent circumcision.Abravanel believes that in the forefront of the men’s minds was one thing: getting their hands on

Jacob’s vast wealth. This, then, is the backdrop to understanding Simeon and Levi’s deadly deed. After

the two killed the villagers, their brothers came and plundered the town.Jacob’s sons taught posterity a lesson in morality, summed up by the sentiment: Fight fire with fire. The

villagers conspired to do harm to Jacob. His sons outsmarted them by taking the initiative. -

Bible Studies: The Story of Judah

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Abravanel observes that chapter 38 digresses from the Bible’s main storyline of Joseph,

training a spotlight on Judah. Why the interlude, Abravanel asks?“And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his

brethren, and turned in to a certain Adullamite, whose name was Hirah.”“And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his brethren”provides key context and

chronology for Judah’s departure. It took place after the brothers sold Joseph into slavery. The majority

of Jacob’s sons were keen to kill Joseph, and had issued a death warrant. Present at the legal hearings,

Judah argued convincingly against capital punishment. As a result, Judah saved Joseph’s life. Selling

Joseph into slavery was the best outcome Judah could manage.Stylistically speaking, the Bible should have followed up chapter 37 – dealing with the sale of Joseph –

with chapter 39, as it pertains to Joseph’s arrival in Egypt. It would read smoothly. Instead, we find

Judah’s story. The interjection comes from left field, per se.Abravanel gleans three lessons, sharing them with Bible students:

1) Historically, Israel has two distinct kingly lines. One gets traced from Joseph through his sons Ephraim and Manasseh. The other hails from Judah, through Perez. Now, Joseph’s sons were born to his Egyptian wife. Hence, that line should not be viewed as legitimate or worthy of the throne. In contrast, Judah’s son’s pedigree ranked, well, royal. It attests to Tamar’s merit and piety, a woman of valor born to righteous Shem, as the Jewish sages taught.

2) The story of Judah highlights his greatness. “And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his brethren…” Judah wanted nothing to do with his cruel brothers who sought to murder Joseph, their innocent brother. Though he eked out an arrangement to spare Joseph’s life, Judah could not reconcile himself with his brothers’ cold-heartedness. Besides, Judah could not bear to see Jacob’s anguish. Abravanel inserts a caveat. Despite Judah’s hard feeling for his brothers, he regularly visited Jacob, showing filial piety.

3) Finally, the story of Judah was written in Scripture for posterity. Bible students, for all time, will see divine providence at work. Here is how. For the ancients, infant and child mortality was commonplace. However, none of Jacob’s children or grandchildren died prematurely, as the Creator kept a vigilant eye over them. The two exceptions were Er and Onan, sons of Judah and his wife Bat Shua. They both died young, as the Bible relates in our chapter: “And Er, Judah’s first born was wicked in the sight of God. And God slew him.”Onan also brought sudden death upon himself: “And the thing which he did was evil in the sight of God. And he slew him also.”

To summarize, Abravanel learns that the story of Judah, though stylistically out of place, imparts

important information that Bible students need to know. -

Bible Studies: The Tower of Babel

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 11, Bible students encounter the inglorious debacle of the Tower of

Babel. Abravanel digs deep into the puzzling storyline. He asks: Where did the generation go wrong?

What underlaid the provocation of the Almighty?“And the whole earth was of one language and of one speech. And it

came to pass, as they journeyed east, that they found a plain in the land

of Shinar. And they dwelt there. And they said one to another: Come, let

us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone

and slime had they for mortar.”Abravanel supplies Bible students with an intriguing, though straightforward, response. Really, he says,

it was a repeat of an earlier and colossal miscalculation that befell Adam, Cain, and their descendants.

We’re talking about a dismal failure to prioritize, to internalize why the Maker made man in the first

place. Abravanel elaborates:God created Adam in His image and likeness. In our context, it means that the Creator fashioned man to

be rational, and acknowledge God in this world. Put differently, man’s raison d’être centers on

perceiving His mighty endeavors. By so doing, man harmonizes and hones his soul.Adam’s task, then, was chiefly a transcendental one. As for God, He provided Adam with a lovely garden,

stocked with abundant, nutritious food and drinking water. Indeed, nature smiled upon Adam and Eve,

and graciously opened its cupboards. First man would not have to lift a finger, let alone toil to live well.

Adam’s only “job” was to recognize his Creator, and live accordingly. Man was meant to live moderately

and enjoy physical pleasures maturely.But Adam missed his cues. A natural life held no appeal. Of creature comforts, he wanted more and

more and more. And so, God expelled Adam from pastoral Eden to a less inviting environment. There, in

humiliation, he would fend for himself in a land cursed by Above.No longer would nature be kind or forthcoming. Adam brought hardship upon himself, all because he

chose to flout the mission that the Maker requested. Backbreaking labor would be his lot. Adam’s son

Cain fared no better. Passion for make-believe amenities derailed him. He farmed an accursed land. Cain

plowed and the soil mocked him; Cain planted seeds and the soil mocked him more. In the end, Cain

resembled a beast of burden, his brow bent over furrows and fields that would yield no more than a

pittance.Abravanel surveys the ill fate of other early man, but for brevity, we omit that part of his discussion and

now turn to the generation who would build the Tower of Babel. Abravanel shows how they, no

differently than their forebears, failed to assume the mantle that God had placed upon them.Understand that God gave sufficient supplies for mankind to subsist. Ample provisions would allow

people to act and live sensibly, while pursuing truth and purpose – nourishing the soul.However, the post-flood generation wanted more. They were not satisfied with a simple and quiet

lifestyle. Instead, they set their sights on building a metropolis, the Tower of Babel its centerpiece.

Urban planners and architects wrote God out of the script. They also rewrote the play book, per se.It became fashionable to buy stuff, acquire things. If it meant stealing from others, well, that presented

no moral problem for people seeking upward mobility. Thievery and murder followed. How different

urban existence compared with agricultural life!Day and night. No longer were folks self-sufficient. For modern society, collectivism stood front and

center. Abravanel quotes King Solomon, who summed it up best: “God made man straight, but they

sought many intrigues.”Though Abravanel writes more, readers get the gist of the point and understand where the generation

of the Tower of Babel went wrong. For the fuller discussion, please seeAbravanel’s World. -

Did King David Sin with Batsheva?

The Biblical narrative in Samuel records one of the most controversial encounters

in the entire Bible—the story of King David and Bat Sheva. This is precisely the

question I put to my Bible study group, which has taken several sessions to work

out, or rather, to work through.A prefatory remark is in order. This discussion is based on the Abravanel’slengthy and thorough treatment of the subject. 1 Abravanel, briefly, is known forhis piercing questions and thoughtful answers; he does not pull punches in hissearch for truth, or as he puts it “the simple truth” or ha’emet hapashut (האמתהפשוט). Abravanel’s comments take Bible students step by step through the eventsrecorded in the Bible. To be sure, for Abravanel, this means a comprehensivereview of Biblical verses 2 as well as the Talmud’s coverage of the controversy. 3Finally, for our purposes here, I present Abravanel’s comments on the Book ofSamuel in fantastic shorthand, essentially a summary or overview of the topic.

Storyline: King David had intimate relations with Bat Sheva, a woman

married to a warrior in the king’s service. From the relationship, Bat Sheva conceived. King David recalled the woman’s husband, Uriah Hachiti, from the

front and urged him to spend time with his wife. Uriah refused to go home,

insisting that the offer offended a noble soldier’s sensitivities. His commanding

officer and fellow soldiers were in the field “roughing it.” After the king’s second

attempt to send Uriah to visit his wife failed, he resolved that Uriah should return

to the front and there be ambushed by the enemy. This resolution came in the

form of a royal directive to Yoav, the commander. Uriah was, in fact, killed by

enemy fire upon his return to duty.Abravanel lists five compelling reasons that point to a straightforward

indictment of David. 4 Conclusion: the king was guilty of heinous crimes; he

perpetrated a mighty wrong. Heaven meted out punishment to the culprit. For his

part, the king exhibited remorse and indeed heartrending contrition.Abravanel then turns to the Talmud’s interpretation of the very same facts.

The rabbis or Chazal take a totally different tack, infusing Jewish tradition and

insight. Not only do they hold the king blameless, but they go a step further:

“Whoever says that David sinned [with Bat Sheva] errs.” 5Where does this leave us? Did King David sin with Bat Sheva?

According to Abravanel, Chazal’s innocent verdict speaks to a legitimate,

alternate dimension of Biblical text or drush (דרוש). This stands in marked contrast

to Abravanel, who is intent on discovering the verses’ plain reading or pshat (פשט).

Abravanel is always reverential of Chazal, while acknowledging the pshat/drush

divergence. The story of David and Bat Sheva eloquently highlights their distinct

respective outlooks. -

Don Isaac Abravanel: The Garden of Eden’s trees

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508), also spelled Abarbanel was a penetrating Jewish thinker, scholar, and

prolific Biblical commentator. In Genesis Chapter 2, he unearths the meaning of the two trees featured

in the Garden of Eden: the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.Regarding the tree of life, Abravanel questions: How is it that the tree bestows eternal life upon

someone who eats of it? After all, anyone who ingests fruit from any tree can only receive those

qualities or nutrients provided by the tree. Since a fruit’s makeup consists of vitamins and minerals that

remain in man’s bloodstream for a limited time, the impact will be finite. Surely, someone who eats that

fruit does not become immortal.Before Abravanel answers the question concerning the tree of life, he poses a parallel one about the

tree of knowledge of good and evil. It is: How could it be that the tree of knowledge, a tree devoid of

feeling or intelligence, imparts knowledge to the person who eats from it? Again, Abravanel asserts that

fruit can only give to the eater that which itself possesses. So, for example, if pears don’t have any

vitamin k (let alone any emotion or cognition), then a person who eats pears won’t derive any vitamin k

benefit. In our context when we speak about the tree of knowledge, it means that anyone who eats

from that tree shall not receive a boost to his/her I.Q. (intellectual or emotional).Now Abravanel answers the two questions, and we summarize. Abravanel cites the Talmudic sages’

opinion who learn that Adam’s constitution was a sturdy one; he was created to potentially live and not

die. The rabbis’ position concerning man’s super longevity is not inconceivable, writes Abravanel.But Adam sinned when he ate from the tree of knowledge. Disobedience to God’s command abruptly

dashed Man’s death-defying potential. Abravanel believes, that had Adam complied with the Creator’s

request, the tree of life would have facilitated a robust life – earning him eternity.Was Adam originally meant to cheat death and live forever? This question requires explanation. We are

not advocating a position whereby Adam inherently shared traits with the stars and planets, designed to

remain permanent fixtures in the heavens. To be sure, man’s makeup at creation cannot be likened to

the celestials that forever occupy the heavens. That is, Adam was not earmarked to dwell on earth and

not succumb to the grave. Instead, had Adam obeyed God, then the Almighty would have repaid him

handsomely; His kindness and compassion could have catapulted Adam, breathing into him a turbo-

charged existence. But, alas, bumbling Adam blew a golden opportunity to skirt death.Abravanel now turns to discuss the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Let us restate our original

suppositions and definitions. In fact, the fruit held no sway over man’s knowledge base, not of good and

evil in a moral sense (because trees cannot convey morals) and not of I.Q. (because trees cannot convey

intelligence). Rather, Abravanel says that the knowledge fruit worked as an aphrodisiac. The more a

person consumed, the more desirous of sex he or she became.As for redefining the tree of knowledge, Abravanel puts forth that In Biblical parlance, “knowledge”

refers to sexual relations. “Knowledge of good” suggests normal and moderate spousal intimacy;

whereas, “knowledge of evil” conveys exaggerated sexual conduct, lechery.God forbade Adam to eat the intoxicating fruit, as excessive sexual behavior would distract him from

religious values. Crucially, the Torah did not frown upon looking at or even touching fruit from the tree

of knowledge. As stated, Heaven blesses man insofar as he enjoys appropriate spousal intimacy.

However, sexual promiscuity will not be condoned by the One Above. Hence, Adam was told not to eat

the fruit.Genesis chapter 2. Based on Abravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan.

-

Don Isaac Abravanel’s Mission Statement

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508), also spelled Abarbanel was a penetrating Jewish thinker, scholar, and

prolific Biblical commentator. It is, of course, nary impossible to pare Abravanel’s encyclopedic and

groundbreaking commentary on the Bible, and reduce it to a short blog. Indeed, where would one start?

How could we sift through the thousands and thousands of pages of his magnus opus, in order to

produce an Abravanel mission statement?In his commentary on Genesis chapter two, Abravanel shares the following thoughts with his readers.

Does it fit as a mission statement? It just might.Genesis begins with the creation story, outlining six days of work. On the seventh day, God rested.

Chapter two delves into the human face of creation, featuring the Garden of Eden, Adam, Eve, and a

seductive snake. On the curious, if not downright dubious venue and cast of personalities, Abravanel

bombards his readers with dozens of questions.- Is the entire story allegory?

- Is the creation of man in God’s image and likeness literal?

- A tree of life, a tree of the knowledge of right and wrong?

- Talking snakes?

These are a sampling of the burning questions and issues that Abravanel poses. They continue for many

pages, crafted with clarity and insight. Before he provides answers, he writes (and I translate from the

Hebrew):“And after all of these points, designed to wake up sleepy heads, I will rise to the occasion. Thoughtful

analysis will be brought to bear, showing one or more ways to approach these heady topics. Text and

context are front and center. When we conclude our discussion, all queries will be answered – without

exception – all firmly based in this chapter’s verses.Verily, the words of God’s Torah are perfect. To be clear, readers will not be asked to suspend or waive

reason, for religion and reason are intrinsically compatible. The ways of the Maker are straight, and

swerve not.”Abravanel, as always, speaks his mind. He asks hard-hitting questions to stimulate interest in Judaism in

general, and Bible study in particular. His method takes into account an in-depth study of the verses,

focusing on their context within the greater narrative. Finally, he asserts that God’s Torah is divine.Is this Abravanel’s mission statement? Humbly, I submit that it is.

Genesis chapter 2. Based onAbravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan.

-

Exodus Chapter 18: Moses Receives visitors

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.“And it came to pass on the morrow, that Moses sat to judge the people.

And the people stood about Moses from the morning unto evening.”Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Chapter 18 speaks of Moses’ reunion with his wife, two sons, and father-in-law.

Abravanel notes that due to the leader’s inordinately busy schedule, he only managed to take one day

off to spend with family. After that, Moses was back at the grind.Jethro observed his son-in-law’s arduous hours serving the Hebrews, and asked him: “What is this thing

that you do to the people? Why do you sit alone, and all the people stand about you from morning unto

evening?” Abravanel fills in the details regarding Moses’ intense workload, listing the prophet’s manifold

duties that gave him no respite. A close reading of the verses reveals much, as we shall now illustrate.“And Moses said unto his father-in-law: Because the people come unto me to inquire of God.” This,

according to Abravanel, stresses Moses as man of God. That is, the Jews waited in line to speak with

Moses in order to learn of the future. Hence, if someone was sick, he would ask if the disease would

subside, or kill him? Perhaps, someone might inquire of the prophet if he could tell him to where his

animals scampered off? Seeing that Moses was privy to “inside information”, if you will, those

individuals who were distressed waited in cue to get answers to pressing, personal needs.Moses also advised people who worked in the camp’s administration or tribal councils. They sought

sagely counsel from their leader concerning travel logistics, for example, or other administrative issues.Still others required Moses’ legal mind to sort out folk’s quarrels and questions of torts etc., as it says:

“When they have a matter, it comes unto me, and I judge between a man and his neighbor.”In addition, Moses attracted another category of visitors. We refer to students who sought to learn

God’s teachings. “And I make them know the statutes of God and His law.” Although Jethro and the

family arrived prior to the Law giving event at Sinai, still Moses had received some divine statutes at

Marah. Eager pupils desired to grasp God’s ethos, His law.Abravanel ties the discussion all together. Moses, he writes, wore four hats, per se. In his role as a

trusted prophet, he revealed the future. As leader par excellence, he advised others how to govern

wisely. Sitting on the court’s bench, he mediated judiciously. Finally, as a pedagogue, Moses

disseminated Torah, educating students in the intricacies of law.Abravanel’s World discusses more of Jethro’s concerns and solutions, so that Moses and the Hebrews

would function maximally and smoothly. -

Exodus Chapter 20:The Ten Commandments

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. We read in Exodus chapter 20 that the Ten Commandments were transmitted to the

Hebrews on Mount Sinai.“And God spoke all these words saying: I am God, Who brought you out

of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. You shall have no

other gods before Me…”Abravanel discusses exactly what makes the Ten Commandments stand out from the rest of the Bible. It

is, not surprisingly, an elaborate discourse. See Abravanel’s World for the entirety of it. Here, we will

share with Bible students Abravanel’s three, salient observations.One has to do with the Speaker – God. In contrast to all of the other divine commandments, only the

Decalogue was from Heaven, sans an intermediary. That is, when it came to the other commandments,

Moses delivered them to the Hebrews, at God’s behest. Not so with the Ten Commandments. Neither

angel or seraph or prophet uttered them; they came directly from Above. On that historic day, the

Creator of heaven and earth descended, as it were, and addressed His nation. Understand, therefore,

the Decalogues’ intrinsic prominence.Two stresses the audience, the Chosen People. With the other commandments, God transmitted them

to a single person, Moses, albeit His specially-designated messenger who had shown himself worthy.

Moses’ brethren were not privy to hear what Moses heard, nor see what he had seen. How different

were the Ten Commandments! Every person, young and old, heard and understood God’s words. The

myriads of Jews were an integral part of the conversation with the Divine. The fire at Sinai they beheld;

the audible voice they heard.Three emphasizes the material upon which the Ten Commandments were written – all etched in stone.

No other verse in the Torah, no other commandment had been so indelibly engraved. Rather, they were

transcribed from God to Moses, who wrote them on parchment. As for the Ten Commandments,

moreover, no engraver’s tool had been utilized. It was the Maker’s handiwork, His imprint upon rock.

Moses hadn’t participated an iota in it.In brief, Bible students are hereby apprised of the Ten Commandment’s uniqueness, their

otherworldliness. The Almighty alone put His imprimatur on them, in a manner of speaking, as

evidenced by the three reasons stated above. -

Exodus Chapter 26: The Making of the Tabernacle

Don Isaac Abravanel, also spelled Abarbanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Exodus chapter 26 continues to discuss the Tabernacle, a topic introduced in the previous

chapter. Abravanel draws our attention to a grammatical inconsistency in our lead verse (“Moreover,

you shall make…”) when compared to the verb’s conjugation in chapter 25 (“Make an ark…and you

shall overlay it with pure gold”, “Make a table…and you shall overlay it with pure gold”, and “Make a

menorah of pure gold…”).Our verse is conjugated in future tense; whereas last chapter’s verbs are

written in the imperative or command form.Abravanel sheds light on the linguistic discrepancy after phrasing the question. Why, he asks, doesn’t

our lead verse use the command form for literary consistency: “Make the Tabernacle…” instead of the

future tense “You shall make the Tabernacle…?”Here is the answer. The previous chapter introduces the commandment to construct the Tabernacle,

“Make Me a Tabernacle.” It uses the command form. That creates a divine fiat to build a Tabernacle.

That earlier chapter then launches into the “how to” aspect of the first three fixtures in the sanctuary:

“Make an ark…of pure gold”, “Make a table…with pure gold”, and “Make a menorah of pure gold…”Bible students will readily understand that the common – and most valuable – building material for the

ark, table, and menorah is gold. Gold, recall, was the first of several building materials that Hebrews

offered in order to finance the sacred enterprise, some others being silver, copper, wool etc.Now to the point. After the last chapter listed those three fixtures made of gold, our chapter provides

the “how to” concerning the Tabernacle itself. What materials went into the Tabernacle’s walls and

partitions? “Moreover, you shall make the Tabernacle with ten curtains…” As our chapter proceeds, we

shall see that parts of the Tabernacle had also been constructed with gold, silver, copper, wool etc.In summary, the earlier chapter foreshadows – in general terms – an impending commandment to build

a Tabernacle, hence the verb is conjugated in the future tense. Our present chapter follows up with the

“how to” manual, including dimensions and the requisite building material to get the job done,

necessitating the command form of the verb.See Abravanel’s World for the full discussion of the Tabernace and its fixtures.

-

Exodus Chapter 29: The Tabernacle Alter

Don Isaac Abravanel, sometimes spelled Abarbanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Toward the end of Exodus chapter 29, the Bible describes the inauguration of the

Tabernacle altar. Two acts readied the altar: anointing oil and the offering of two daily sacrifices.“Now this is that which you shall offer upon the altar: two one-year-old

lambs each and every day. The one lamb you shall offer in the morning,

and the other lamb you shall offer at dusk.”Abravanel questions: Why does the inauguration ceremony require only the daily sacrifices, but not

other sacrifices such as the sin or guilt offerings etc.? Abravanel also urges Bible students to pay close

attention to the daily sacrifices, one brought in the morning and one in the afternoon. Yet, when it

comes to the festival additional sacrifices, for example, they were brought to the altar at the same time.See Abravanel’s World for the full discussion of the inauguration of the altar. For now, however, let us

address Abravanel’s questions raised above. His answers contribute to understanding an integral part of

Jewish belief and thought, or to restate, God’s mindset, per se.The verses, Abravanel holds, come to disabuse a gross misconception regarding the Creator. That is, God

has not made man with an inclination to sin. Furthermore, the Maker does not desire a pattern whereby

man transgresses, begs God for forgiveness, and concludes the cathartic process with sin offerings.Patently false. To be clear, the Creator did not establish a regime of sin/guilt offerings to be offered on

the altar after the Golden Calf affair, illustrating some inherent moral shortcoming which tilts people to

falter and stumble. And then, because man sinned, he needs sin/guilt sacrifices.Such a mindset, Abravanel teaches, is fundamentally fallacious. Let us review this chapter, and put it in

the proper context. It begins with an overview of the induction of Aaron and his sons into the

priesthood. They were selected to serve in the Tabernacle. Next, we read about the inauguration of the

altar – its anointment and sacrifices. “Now this is that which you shall offer…The one lamb you shall

offer in the morning, and other lamb you shall offer at dusk.”The takeaway: God would prefer for man not to err. How lovely it would be if people walked the straight

path, and not stray! How wonderful it would be if Aaron never had to assist his brethren in getting back

into God’s good graces, if you will! Had the consecration of the altar included sin and guilt offerings,

people would get the wrong idea. Hence, the dedication ceremony included only daily sacrifices.

Heaven’s sublime message rings clear: If only people would obey My commandments and not

transgress, My altar would be content with the daily offerings! -

Genesis Chapter 15: Divine Providence

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Genesis chapter 15, Abravanel imparts, is rich in material. He arrives at this conclusion

after considerable study, as he writes. We share a snippet from his intriguing comments, one that is sure

to stand Bible students in good stead. For the fuller discussion, see Abravanel’s World.“After these things the word of God came unto Abram in a vision, saying:

Fear not, Abram. I am your shield. Your reward shall be exceedingly

great.”“After these things, the word of God came unto Abram…” God pays close attention to the affairs of man.

Providence is the interface between the Maker and man. That is a truism when we speak of common

folk. It is especially true when we speak of prophets. In that vein, Abravanel introduces an important

question on chapter 15’s opening verse quoted above: Why did God appear to Avram at this particular

juncture, and what was His message to him?In Chapter 14, we read that Abram had just succeeded in pulling off an extremely impressive military

victory over an army far superior in numbers than his. How did that change Abram’s life? According to

Abravanel, it changed everything!Abravanel theorizes. Before the patriarch handed his royal opponents a drubbing, and prior to Abram

restoring the captives and chattel to the king of Sodom, life for the patriarch was carefree. A picture of

serenity.That changed après la guerre. Anxiety gripped Abram. Gone were halcyon days, when worry and angst

were unknown. Gone were the quiet days and nights, when the patriarch was footloose and carefree.

Abram’s military feat carried concerns of revenge. As Abravanel puts it, noble warriors don’t take

military setbacks lightly. They will retrench and keep a peeled eye open for the right opportunity to

avenge their honor.In practical terms, that meant Abram required around the clock bodyguards – lots of them. The

patriarch understood that his days of working as a farmer were a thing of the past. Thoughts of ruthless

and crafty adversaries preoccupied him.Abram’s sweet and uninterrupted sleep after toiling in the fields was history. In the patriarch’s mind,

nighttime filled with horror, fright. Daytime offered no respite. Wherever Abram turned, he saw sword

toting bodyguards, reminding him of his new reality.It weighed heavy upon the patriarch, especially because he was unused to restraints. Abram felt that his

life hung in the balance. In a flash, battle cries could erupt, fueling further tension.Abram’s angst didn’t stop there. Ever since he returned the chattel to the king of Sodom, he fretted. His

stomach ached to consider what he had done. Was it morally reprehensible to return the loot over to a

king and his countrymen who were evil and rotten to the core, sinners against the Almighty’s values? Far

preferable, Abram questioned, had he kept it for himself. With that money, he could have funded and

fed his soldiers, now patrolling 24/7.In both regards, Providence soothed the patriarch’s sore soul. “Fear not, Abram. I am your shield.” He

heard God’s assuring words. Abram need not think about existential threats from enemies, nor did he

need bodyguards. God had his back.Further, when it came to returning war spoils to the king of Sodom, the Creator let the patriarch know

that he need not second guess himself. Abram’s altruism was apt. “Your reward shall be exceedingly

great.”Heaven would shower blessing and bounty upon the patriarch. He learned that since the King of

Kings would reward him, it would be an affront to accept gifts from mortal kings, even small ones. -

Genesis Chapter 48 : Jacob's Final Days

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Chapter 48 brings Bible students closer to Jacob’s final days. The patriarch summoned

Joseph, as our chapter recounts. The blind patriarch revealed to Joseph divine secrets about the future,

a destiny that Heaven laid bare before him in Luz, decades earlier.“And Jacob said unto Joseph: God Almighty appeared unto me at Luz in

the land of Canaan, and blessed me. And said unto me: Behold, I will

make you fruitful…. And I will make of you a company of peoples, and

will give this land to your seed after you for an everlasting possession.

And Israel beheld Joseph’s sons, and said: Who are these? And Joseph

said unto his father: They are my sons, Whom God has given me

here…Now the eyes of Israel were dim for age, so that he could not

see.”Abravanel zeroes in on the father-son dialogue. Jacob, as stated, revealed to Joseph that which the

Creator had foretold in Luz. Mysteries galore. Now, as he lies dying, the hoary patriarch could make out

shadows of two men within earshot, hearing Jacob’s divine secrets. It prompted Jacob to ask: “Who are

these?”Answering, Joseph responded: “They are my sons, Whom God has given me here.”Abravanel asks concerning Joseph’s answer: Why did Joseph tell his father that God had given him two

sons in Egypt? Jacob, of course, knew that when Joseph went to Egypt, he was single and had no

children.Abravanel clarifies what Joseph meant. Jacob realized that his private conversation with Joseph, was,

well, not private. Two others had been present, eliciting the visually-impaired patriarch’s curiosity:

“Who are these?” Joseph had been listening intently, as his father revealed the future, things he had

heard in Luz. “They are my sons, Whom God has given me here,” Joseph replies.Joseph wanted to show Jacob that he understood God’s prescient message, uttered in Luz. “Here” does

not refer to location – Egypt. The fact that Ephraim and Manasseh were not born in Canaan was

abundantly clear. Instead, Joseph conveyed the reason behind his fathering two sons in Egypt. “They are

my sons, Whom God has given me here.” That is, as Joseph processed and internalized what God had

foretold to Jacob in Luz.“And said unto me: Behold, I will make you fruitful…And I will make of you a company of peoples…”

Because of that prophecy spoken in Luz, Joseph comprehended that he had been blessed by Above with

these two sons. Put differently, Joseph realized that elements of the Luz communication materialized. As

a consequence of God’s promise, he had fathered Ephraim and Manasseh in Egypt. -

Introduction to the Book of Exodus

Exodus (Shemot in Hebrew) segues from Genesis (Bereshit), for good reason.Here are four rationales that explain what takes us from the Torah’s first to second book.1) Bereshit dealt with individuals of great personal stature. To name some of the moral giants, welist: Adam, Noach, Shem, Eiver, Avraham, Yitzchak, Yaakov and his sons. There were otheroutstanding personalities, as well. After the narratives of these men of note were completed,Sefer Shemot commenced. Emphasis changes track from holy individuals to the holy Hebrewnation. Given the private/collective parameter, really, the Torah’s first book could aptly becalled “The Book of Individuals”; the second book “The Book of the Nation.”2) A second rationale requires a deeper look, addressing the bedrock question: Why did Godtransmit the Torah? Answer: He desired to refine the Chosen People, His flock, througheducation and mitzvot. Scripture and its teachings uplift and enlighten body and soul. However,when the divine Torah sought to chronicle this unique and holy people, it first provided theirbackstory. In the beginning was their family tree. Indeed, worthy stock, blessed by the Maker.The Jews hail from a dedicated and close-knit religious-minded community. Remarkable menhoned their descendants for nobility.Of course, all mankind descends from Adam and the Torah is saying more than who begot whom.Bereshit, metaphorically speaking, is a story about separating the wheat from the chaff, fruit from itspeel. The men of renown are likened to what is ethically precious, morally craven descendants of Adamto byproduct discarded. Adam’s third son, Shet, was a cultivated, sweet fruit, a towering individual, astriking figure etched in God’s image.But not all of Shet’s descendants stayed the course. Many fell into the fruit peel category. Jews were ofa different ilk. In time, Noach arrived, “a pure, tzaddik” to quote Bereshit. 6 The Torah relates that Noachfound favor in the Creator’s eyes. Yet, again, not all of the ancient mariner’s sons followed God.Specifically, Cham and Yafet didn’t, and are thus relegated to chaff, summarily dismissed. Shem, incontrast, held the flame, as did his great grandson Eiver, as did his great grandson Avraham. Avrahamhad it all, a delectable fruit, an indefatigable doer of good and a constant truth seeker. Of his offspring,Yitzchak shined most brightly, all others marginalized. From Yitzchak came Yaakov. While Esav wasdetested, Yaakov rose in stature, a veritable Torah-value repository. Yaakov’s twelve sons clung to theirfather’s ways, all glimmering wheat stalks. Together, father and sons forged the holy nation, each onesteadfast to Torah principles.And the Maker rewarded them, showering them with divine favor or providence. 8 In sum, the role ofBereshit provides an important contribution to understanding the roots of the Jewish People, theirancestry. Shemot recalls the greatness of the nation, and its religiosity.3) The Torah’s first book conveys the mighty deeds of the patriarchs, their holiness and divinecommuniqués. Hence, we read about the lives of Adam, Noach and his three sons, and all of theirsuccessive generations. This is by way of background until we reach Avraham. Avraham’s wholenesssurpassed that of his predecessors. This observation is borne out by the fact that the Torah writes threeparshiyot about his lifetime. For Yitzchak, the Torah dedicated one entire parashah. And in testimony toYaakov’s and his son’s prominence, we count three pashiyot. Yosef and his brothers comprise Bereshit’sfinal three parshiyot. All tallied, the Torah’s first book consists of twelve parshiyot, all training a light onthe patriarchs’ positive traits and contributions.Moshe’s attainments, by contrast, soared above the rest, equal to the sub-total of them. And in the fieldof prophecy, he far outdistanced them. That explains why Shemot’s twelve parshiyot pertain to the seer.In that regard, Bereshit’s scorecard, if you will, hints at the predominance of Moshe. An entire bookbelongs to the prophet, one equal to the Torah’s first book. Bereshit’s subjects are the patriarchs (andtheir forerunners); Shemot’s subject matter is Moshe.4) Finally, the divine Torah writes the epic story of how God took in His flock, the House of Yaakov. Butfirst, readers needed to learn of Avraham’s, the first patriarch’s, sterling character. Still, Avraham hadnot been born into a vacuum. His illustrious forebears, to name some, were Adam, Noach, Shem, andEiver. Avraham, morally and ethically evolved from them.Within Avraham’s story we read about a divine covenant, known as the brit bein ha’betarim. It foretells,“Your seed shall be strangers in a strange land.” The covenant or brit also spoke of prodigious offspring,and a Holy Land which they could call home. Finally, in that brit, Avraham learned that God wouldextend His providence over the patriarch’s descendants, and His close attachment or devekut to them.The balance of Bereshit reveals how covenantal promises play out. Thus, for example, we read aboutYaakov’s and Esav’s intrauterine posturing. Later, there was a noxious sibling rivalry between Yosef andhis brothers. Finally, a fierce famine forced Yaakov’s and his family’s descent into Egypt. Sowed were theseeds of national exile and redemption.Bereshit, then, lays the prefatory foundation upon which Shemot may be built. Put differently, theTorah’s first book introduces the ills and travails that precipitated a multi-century exile, one withdisastrous consequences for the fledgling nation.It also opened a window. At the end of the calamitous sojourn in Egypt’s hell, salvation came – theexodus. That was only the half of it. On Sinai, the Hebrews acquired the requisite skillset to reachreligious heights. Divine providence and the Shechinah nestled into the people’s desert camp, housed inthe Tabernacle or Mishkan. To sum up, Bereshit brings the root causes (rivalry and famine); whereas,Shemot discusses the consequence (read: the second book elaborates on exile and exodus).We now better appreciate the divine wisdom that sequenced the order of Bereshit’s and Shemot’s parshiyot. As for the author, all had been transcribed by Moshe, at the word of God. Moreover, the prophet received commentary on all that the Creator communicated to him. After we have laid out these four introductory rationales, we proceed to Shemot’s commentary, with God’s help.

Page 2 of 3