-

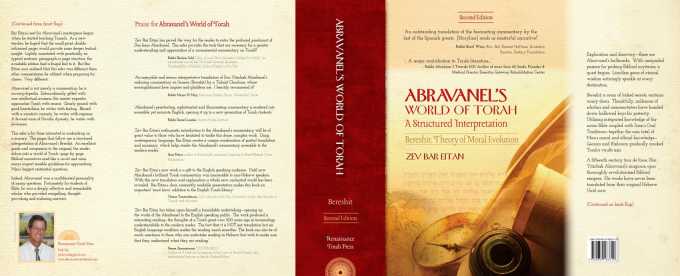

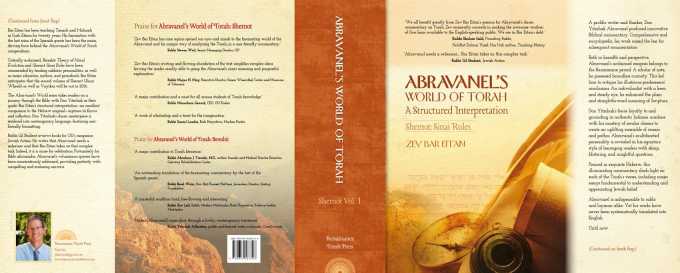

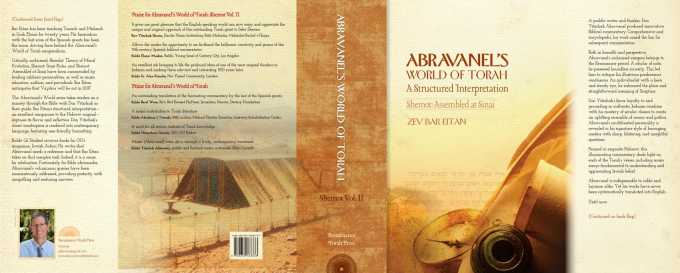

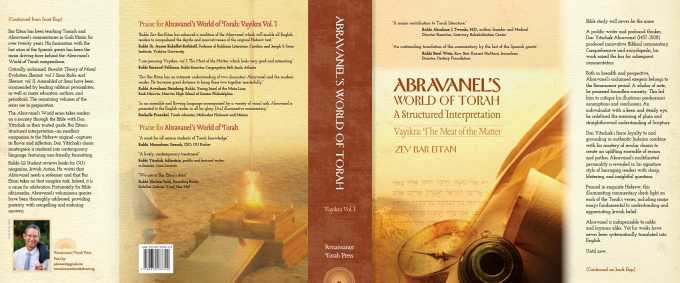

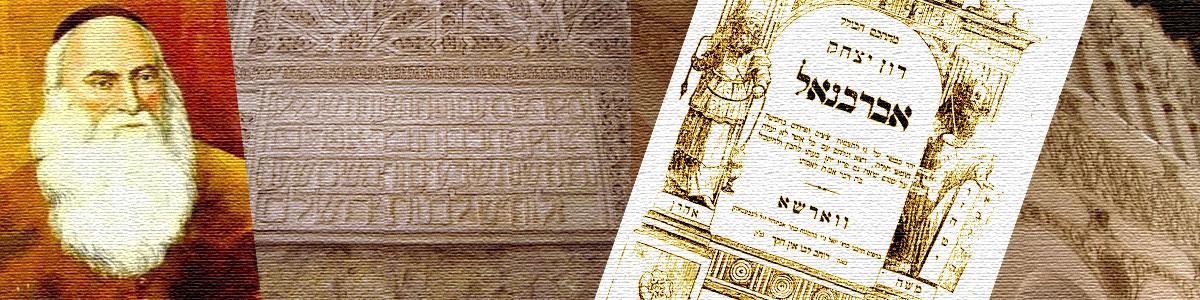

Abravanel’s World of Torah

is an enticingly innovative yet thoroughly loyal rendition of a major fifteenth-century Hebrew classic.

For the first time, Don Yitzchak Abravanel’s Bible commentary has become accessible IN ENGLISH.

Abravanel’s World of Torah: Series

Genesis

-

Bible Studies: Jacob Leaves Home

“Now therefore, my son, hearken to my voice and arise. Flee to Laban

my brother, to Haran.”Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 28, Jacob is urged to leave home. The precise destination is less clear.Jacob’s mother Rebekah instructs him to travel to her brother Laban: “Flee to Laban my brother, to

Haran.” Jacob’s father Isaac had something else in mind: “And Isaac called Jacob, and blessed him…and

said unto him: Arise, go to Paddan-Aram to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father.”Abravanel makes sense of the seeming ambiguity surrounding Jacob’s destination. Along the way, he’ll

do more than provide Bible students with an address. Abravanel will also fill in some nagging blanks

about Isaac and Rebekah.In the aftermath of the high drama associated with Isaac’s blessing, things got messy. Rebekah

overheard Esau’s desire to murder Jacob. According to Abravanel, Rebekah never did tell Isaac that she

masterminded the efforts to secure the patriarch’s blessing for Jacob. Had she done so, Isaac would

have pinned the ensuing family dissension on her. But it seems like the aged patriarch remained

blissfully unaware of the boiling hatred and contempt Esau held for his younger brother.Instead, Rebekah told Isaac a white lie, let us call it. “And Rebekah said to Isaac: I am weary of life

because of the daughters of Heth. If Jacob takes a wife of the daughters of Heth….what good shall my

life do me?”Stressing marriageable material, she urged Isaac to send Jacob away to Laban, in order to

find a suitable wife.But actually, Rebekah had something else in mind. She believed that Laban, her young and burly

brother, would protect Jacob, should Esau show up looking for a fight. Isaac, as written above, was

unaware of the intrigue, as well as the hostilities the intrigue stirred. Isaac took Rebekah’s words at

face value. That is, Jacob needed to leave home posthaste in order to find a wife.Isaac directs Jacob differently than Rebekah. “And Isaac called Jacob, and blessed him, and charged

him, and said unto him…Arise. Go to Paddan-Aram to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father.”

Abravanel learns that there is more to our story than different addresses. For Isaac, Jacob’s destination

should be Rebekah’s father, not brother. Why? Since the patriarch assumed the goal centered on

locating a good match, Bethuel would be the better contact. As an older and more mature man than

Laban, his judgment would be sounder, and thus be more helpful for the task at hand: matrimony. -

Bible Studies: Jacob Returns Home

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 32, Jacob begins his trek home. The first leg of his journey starts

auspiciously; angels huddle around him.“And Jacob went on his way, and the angels of God met him. And Jacob

said when he saw them, This is God’s camp, and he called the name of

that place Mahanaim. And Jacob sent messengers before him to Esau

his brother…”Abravanel probes Jacob’s mindset, as he parted ways with Laban, a most trying man. “And Jacob went

on his way, and the angels of God met him.”Long years under Laban’s roof and employment had sapped

the patriarch’s strength. Seeing Laban and company shrink into the horizon gladdened Jacob’s heart and

put a bounce in his gait. He breathed a sigh of relief. Unburdened.Invigorated in body and soul, Jacob regained his prior energy level. Elated, he received prophecy, the

same as he had experienced when he left the Holy Land. At that time, he beheld a vision with a ladder.Now Jacob saw something else. “This is God’s camp”, the patriarch declared. Abravanel deciphers the

telling image, explaining that “God’s camp" refers to divine providence – and more. “Camp” carries

military overtones. According to Abravanel, the vision boosted Jacob’s morale. “And he called the name

of that place Mahanaim.”In Hebrew, “Mahanaim” means camps, in plural. Heavenly agents would join

forces with Jacob’s men. Together both camps would rally to defend and protect Jacob and family.Abravanel investigates our verse more thoroughly. “And Jacob went on his way, and the angels of God

met him.”He asks: Who were these angels of God? Were they, as we posited above, the heavenly sort

of beings, relaying the Creator’s message to the patriarch? The problem is, as Abravanel notes, they

didn’t relay anything to him. Furthermore, the verb “met” seems peculiar. Better, the verse should have

said that these angels appeared to Jacob.Abravanel suggests the following. When Jacob bid farewell to Laban, he didn’t know that the road he

chose to take him home was on a collision course with Esau, his brother. Had Jacob known, Abravanel

writes, Jacob would have opted for an alternative route so he could avoid the fraught confrontation.Abravanel provides two distinct approaches in determining the identities of the “angels of God.” One,

the patriarch beheld a divine image. It was of the Maker’s angels converging upon him. They encircled,

giving Jacob a sense of safety. Silently, they surrounded him. No enemy would penetrate God’s lines of

defense. “And Jacob said when he saw them, This is God’s camp.”After Jacob saw the angel’s formation,

he felt less apprehension about the imminent encounter with Esau. Jacob’s side outnumbered Esau’s.Here is Abravanel’s second approach to reveal the identity of the “angels of God.”These angels weren’t,

well, the angelic type. They were merely passersby. As is the wont of travelers, Jacob struck up a

conversation with them. One thing led to another. It came out that these travelers casually mentioned

to Jacob that just down the road, in the direction Jacob was heading, they had seen a band of soldiers.

When Jacob questioned his new friends further, he ascertained that the warriors were none other than

Esau and his men. For Jacob, the “casual” meeting with these travelers proved invaluable and timely.

And as we shall see later in this chapter, Jacob will prepare himself accordingly. For the religiously-

attuned patriarch, these travelers were indeed angelic. -

Bible Studies: Lot's Daughters

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis Chapter 19, we read about Sodom and Gomorrah’s destruction. Only Lot and

his unwed daughters survived. However, the Bible makes clear that their own merits had nothing to do

with it.“And Lot went out unto them to the door, and shut the door after him.

And he said: I pray you, my brethren, do not so wickedly. Behold now, I

have two daughters that have not known man. Let me, I pray you, bring

them out unto you and do you to them as is good in your eyes….”Lot’s daughters are mentioned twice in Chapter 19. In this blog, we focus on Lot’s dilemma with the

townspeople, and his gambit – at his daughter’s expense – to protect his otherworldly visitors.As the verses above teach, Lot offered the lustful neighbors his two virgin daughters, if only Sodomites

would go away and leave his guests alone. Putting aside the moral messiness of the scheme, Abravanel

poses the following query: What was Lot thinking?Earlier in Genesis, Abravanel theorizes as to the main, ethical issue plaguing Sodom and Gomorrah. Hint:

it wasn’t about sexual immorality. Rather, Abravanel posits that the numero uno shortcoming, and a

huge one it was, had to do with their clenched-fist policy when it came to sharing financial success with

the less fortunate. Sodom and Gomorrah’s fields and farms grew crops prodigiously, year after year. The

citizens were loaded, flush with cash.Sodomites took their miserliness seriously, going so far as to legislate rules & regulations regarding poor

folk: They were not to trespass. If a beggar, Abravanel continues, came looking for handouts, they would

be sexually assaulted and humiliated, before being run out of town. Charity didn’t exist, an anathema to

Sodom’s ethos.Given that background, Abravanel asks: If Sodomites sought to keep the indigent away, what purpose

would it serve for Lot to offer his daughters to the local sickos? As stated, sex wasn’t the main driver.Irate Sodomites presumed that Lot was harboring strangers in their land, men who had NO business

being there. The crowd’s intention had been to manhandle Lot’s guests, and thereby create a deterrent

whereby such things would never occur again. Abravanel stresses that the neighbors didn’t have a beef

with the newcomers. Perhaps they were unaware of Sodom’s laws. However, they did hold Lot

responsible. He should have known better than to host guests.Abravanel suggests that Lot came up with the following gambit, and thus pleaded with the Sodomite

mob to take his daughters. Lot surveyed the rowdies surrounding his house, banging on the door. He

assumed that among the frenzied masses were his own sons-in-laws, Sodomites married to Lot’s

daughters. Lot figured that when he pushed his virgin daughters out the door, the girls’ sisters would put

up a fuss, demanding their husbands keep their fingers off the girls. Once that happened, Lot hoped, a

new dynamic would emerge, creating chaos. In the ensuing confusion, Lot would sneak his guests out of

town. Thus, Abravanel explains Lot’s gamble. -

Bible Studies: Noah the Righteous

“These are the generations of Noah. Noah was in his generations a man

righteous and whole-hearted. Noah walked with God.”Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. In Genesis chapter 6, the Bible focuses on an exemplary personality: Noah.In glowing terms, the Bible extols Noah as righteous and whole-hearted. Abravanel takes a deeper dive

into this survivor’s stout soul, showing ways in which Noah exceled in an era when a world tottered and

tanked. Indeed, as Noah’s neighbors corrupted their ways and wallowed in morass, “Noah walked with

God.”Abravanel quotes a rabbinic epigram that best contrasts the values of virtuous Noah from his

unscrupulous contemporaries. The translation of the witticism goes like this: While mankind gorged

their bodies and starved their souls, Noah nourished his soul, and starved his body.In what ways did Noah please his Maker? “Righteous” refers to Noah’s interpersonal relationships. With

his fellow man, Noah was honest. He took pains to treat each person fairly, courteously. This is in

marked contrast with those around him. The generation was more than inconsiderate to others; they

were mean-spirited and deceitful.There was a second aspect that distinguished Noah from his contemporaries. Decency defined him.

His attitude toward the physical world and its pleasures came without misplaced hype. Noah

displayed steely self-discipline to material things. As for the rest of the planet, moderation was not in

their lexicon. Nor was fair play.Whim ruled. Bigtime. Gluttony proved their undoing. Man and animal alike acted out unnaturally in

pursuit of perversion.Abravanel adds something else about Noah. Despite a dystopian culture of sin, Noah stood apart. For

him, crisp demarcation lines divided right from wrong. Smut held no sway over him, let alone blur God’s

ethos. From youth until old age, Noah’s swerved not an iota from divine service. Through hell and high

water, “Noah walked with God.” Literally.Readers will find that Abravanel details, and heaps, more praise for Noah in Abravanel’s World.

However, before concluding this blog, let us share one aspect of Heaven’s favor and divine providence

for loyal Noah, as per Abravanel’s understanding.Genesis’ first chapters record a meteoric population growth trajectory, with early man begetting and

begetting and begetting. Yet, Noah’s family was, to be colloquial, nuclear in size. He fathered only three

sons. Abravanel learns that, typically, a father of many children cannot fully devote himself to his kids’

education. Had Noah’s family waxed many, undoubtedly, some of the sons would have been influenced

by a wayward world. However, because Noah’s number of children was small, he kept a keen eye out for

creeping unacceptable attitudes and behavior. A vigil dad will nip trouble in the bud.Abravanel says more. He understands that Noah did not father daughters. Had he, then, perforce the

daughters would have married men – all rotten to the core. Noah’s grandchildren would have followed

the despicable ways of their fathers. As a case in point, Abravanel brings an example from Lot’s

daughters. When Sodom and Gomorrah fell to fire and brimstone, so too did Lot’s married daughters.Based on Abravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan

-

Bible Studies: The Binding of Isaac

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 22, we read of the binding of Isaac. This blog covers a small snippet of

Abravanel’s preface. He asserts that, arguably, this is one of the most defining and dramatic chapters in

the entire Bible. Abravanel’s discourse is precious, and lengthy. For the full discussion, please see

Abravanel’s World.“And it came to pass after these things, that God did prove Abraham,

and said unto him, Abraham. And he said, here am I.And He said, take now your son, your only son, whom you love – even

Isaac – and get you into the land of Moriah. And offer him there for a

burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell you of.”Now to some of Abravanel’s opening remarks. The binding of Isaac presents Bible students with a

cornerstone of Jewish faith. On the merit of the event, Hebrews stand in good stead with their Father in

heaven. The story has been told and retold, generation after generation. Jews know it by heart. The

binding of Isaac forms a backbone to Jewish prayer and liturgy. These, then, are compelling reasons to

study the subject intently, more so than other chapters.When writing his Biblical commentary, not surprisingly, Abravanel did not work in a vacuum. Before he

delved into the binding of Isaac, he first familiarized himself with his predecessors’ and contemporaries’

approaches. What did they say?Figuratively Abravanel likens himself to a field hand who walks behind other harvesters who dropped

their sheaves. When a stalk pleases him, he picks it up and puts it in his satchel. If a stalk displeases him,

he rejects it, always pushing on with his search for the choicest produce. In this manner, Abravanel

develops and hones his classic essay on the sublime story of a father and son, Abraham and Isaac.

Abravanel offers a prayer to the Maker, asking for insight and eloquence.As is his wont, Abravanel begins with a sweeping historical overview – and a probing question. What was

the main point of God’s test of Abraham?Abravanel starts with Adam, the first man. In a word, he failed to thrive in the task given to him by God.

How? Of the two noteworthy trees in the garden of Eden, Adam gravitated to the tree of knowledge.

That tree represented superficiality and focused on things material. The fruit of the tree of knowledge

captivated him. It proved his undoing because God expected more from man than merely the mundane.The tree of life, symbolizing the Creator’s ethos, held no interest for Adam. Hence, God ushered him and

Eve out of the idyllic environs, to toil the land, and reconsider man’s purpose in the world.The misstep that tripped Adam, according to Abravanel, has distracted his descendants ever since – day

in and day out. Alas, people have been barking up the wrong tree, so to speak. The ethics of the tree of

life, the tree that carries the banner of moderation and maturity, hardly gets any attention. That fruit

urges man to forge a relationship with the Almighty.Enter the great flood. Divine wisdom saw fit to unleash a deluge. It mopped up a misguided civilization.

Only Noah and his family survived. Shortly, the masses’ embraced hedonism, as if groping in the dark.

Frivolity reigned supreme. Déjà vu.Civilization tottered.

But then, hope flickered. Abraham emerged. Out of a milieu of moral confusion and chaos, he figured

things out and put his faith in God. Abraham believed and preached Heaven’s message: God is in charge.

He governs the world.Pure intellect brought him to that conclusion. He had discovered the truth. Abraham, Abravanel teaches,

was the first to apply analytical reasoning to bear, in coming to his revelation. He couldn’t keep his

findings to himself, disseminating the truth about the Almighty to whomever. “And he built there an

altar unto God, and called upon the name of God.”That is, Abraham was the first one who recognized

God’s omnipotence, ruler of all. Determinedly, the fiery prophet introduced God to mankind.As stated, for Abravanel, Abraham had arrived at the truth through penetrating study and analysis. For

it, the Almighty smiled upon him. Divine wisdom resolved once and for all – Abraham’s seed would

become the Chosen People.And then the Almighty appeared to Avraham with a request. Characteristically, the prophet didn’t flinch,

as the Bible records. “And he said, here am I.”In short form, herein is background to the ultimate religious test and quintessential religious response.

-

Bible Studies: The Cave of Machpelah

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 23, Sarah passes away. As we shall see, Abraham leaves no stone

unturned in efforts to secure an honorable burial spot for his beloved Sarah.“And Sarah died in Kiriatharba, the same is Hebron, in the land of

Canaan. And Abraham came to mourn for Sarah, and to weep for her.And he spoke with them saying, If it be your mind that I should bury my

dead out of my sight, hear me, and entreat for me to Ephron the son of

Zohar…that he may give me the cave of Machpelah, which he has,

which is in the midst of you for a possession of a burying place.”Abravanel asks: Of all places in Canaan, why did the patriarch set his sights exclusively on the cave of

Machpelah to inter Sarah? Wouldn’t any place in the Holy Land accord the first matriarch honor?The Bible, Abravanel explains, places great importance on burial. Moreover, location matters. Here is

why. Man is comprised of body and soul. Add another factor: God punishes or rewards, depending on

how a person lived his life. If he followed God’s ways, his refined soul will garner high spiritual marks.

That soul will find its eternal rest in heaven, specifically in a befitting, spiritual realm or designation.Now discussion turns from the deceased, righteous person’s soul to his lifeless body. Assuredly, the holy

person’s physical frame, too, deserves apt interment. No different than the soul, so too the physical

place of burial should reflect that person’s lofty accomplishments, while alive.Abravanel is explicit. It is more than a mere slight for a pious individual’s body to be buried and lie next

to an evildoer’s body; it’s positively indecorous. Just as their respective souls do not share the same

otherworldly space, so too their bodies should not lie side by side.Thus far, Abravanel generalizes about burial rules. But what about our verses quoted above? Why did

Abraham insist on the cave of Machpelah for Sarah? He posits that even within the Holy Land, some

plots are superior to others. Perhaps soil quality plays a role in grading plots. Geography can as well. In

what way?Abravanel learns that some ground types will more quickly absorb and dispose of a deceased’s body.

Decomposition aids the soul’s ascension into the heavens, and helps bring catharsis to the dead. “And

does make atonement for the land of His people.”Furthermore, custom or habit plays a part. Thus, if a particular or designated area has been a cemetery

for people of renown, generation after generation, that ground becomes hallowed by association.

Osmosis.Abravanel likens the ground where the righteous are interred to a mantle used to cover and adorn a

Torah scroll – holy by association.Abraham had these sentiments and sensitivities in mind when he planned Sarah’s funeral arrangements

in the cave of Machpelah. That precluded burying the matriarch next to Canaanites, a nation infamous

for irreligious conduct. “After the doings of the land of Egypt, wherein you dwelled, shall you not do.

And after the doings of the land of Canaan, where I bring you, shall you not do. Neither shall you walk in

their statutes.”Instead, Abraham sought a special place for his wife, one that matched her uniqueness. The cave of

Machpelah would make a perfect fit, perhaps attesting to tradition that Adam and Eve had been buried

there. Later in the Bible, when Jacob felt his death nigh, he beckoned Joseph and requested to be buried

next to his parents and grandparents in the cave of Machpelah.In closing, Abravanel learns that Abraham’s example and legacy provide thoughtful guidelines on burial

practices. -

Bible Studies: The Patriarch and the King

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 14, the Bible chronicles Abram’s dashing military success, which freed

Lot and the other captives who were snatched from their homes in Sodom, and led away.“And the king of Sodom said to Abram: Give me the persons, and take

the goods for yourself. And Abram said to the king of Sodom: I have

lifted up my hand unto God, the God most high, Maker of heaven and

earth, that I will not take a thread nor a shoelace nor anything that is

yours, lest you say: I have made Abram rich, except only that which the

young men have eaten, and the portion of the men who went with me,

Aner, Eshcol, and Mamre. Let them take their portion.”Further, the Bible records a conversation between Abram and the king of Sodom. It turns on the

question of war spoils. The patriarch, out of strong feelings of family ties for his captured nephew Lot,

risked everything to save him. In a daring military raid, under cover of night, Abram and his Canaanite

allies, saved the day. All of the Sodom prisoners, together with that city’s chattel were wrested away

from the enemy. The valorous patriarch was greeted by a jubilant king. Sodom’s royal highness desired

to reward commander Abram handsomely, legitimately so.Abravanel is puzzled by Abram’s refusal to accept the prizes of war, offered by Sodom’s monarch. Fair is

fair. From time immemorial, there have been conventions about these matters. Victorious warriors were entitled

to the lion’s share.Why, Abravanel asks, did the patriarch turn the king down? Abravanel goes further, questioning if the

patriarch exhibited hubris by declining the king. Indeed, Bible students need to understand Abram’s

position. What was he conveying or signaling?Abravanel lays important groundwork into morality. He says that it comes down to honing ethical

excellence; at least one aspect of it: gift giving and gift receiving. In a word, the moral man works within

a well-guarded milieu. He fraternizes with like-minded truth seekers.When the patriarch refused the king’s munificence, he conveyed a not-so-subtle message. That is,

Abram was not interested in befriending the king of Sodom. Why?Sodomites weren’t just licentious, though that would have been enough to turn Abram’s stomach. They

were heartless to the poor and needy, enshrining it in their bylaws and local governance.Of course, the patriarch wanted nothing to do with it, for it was an anathema to his refined inner fiber. A

king of Sodom is still a Sodomite and Avram was discerning when it came to choosing friends.And thus, the patriarch spurned an injudicious alliance with Sodom’s king, stating: “I will not take a

thread nor a shoelace nor anything that is yours…” -

Bible Studies: The Rape of Dinah

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Genesis chapter 34 covers the violent rape of Dinah, and subsequent revenge killings

carried out by her brothers.“And Dinah the daughter of Leah, whom she had borne unto Jacob, went

out to see the daughters of the land. And Shechem the son of Hamor the

Hivite, the prince of the land, saw her. And he took her, and raped her,

and humbled her.”Abravanel provides Bible students his perspective on the crime and punishment. Given that Shechem

son of Hamor committed the rape, was it excessive punishment to massacre all the men of the village,

Abravanel asks? “And it came to pass on the third day…that two sons of Jacob, Simeon and Levi, Dinah’s

brothers, took each man his sword…and slew all the males.”And, if we put forth that Jacob’s sons sought to avenge Dinah, why did they subsequently pillage the

place? “And all their wealth…they took…even all that was in the house.”Abravanel asserts that revenge,

if it is to be morally defensible, must adhere to strict parameters. Certainly, greed cannot enter into the

equation. Thus, after Jacob’s sons killed the men and rescued Dinah, why did they take booty?Abravanel dives into the chapter devoted to Dinah’s rape – and repercussions. He bases the discussion

on the legal/moral code that was widely accepted and practiced by the ancients. We speak of the

Noahide laws. That code, among other things, forbade promiscuity and stealing – on penalty of death.These are Abravanel’s prefatory remarks. In that light, Dinah’s brothers must be judged, Abravanel

posits. Rape, of course, violated the law. Stealing, also, infringed Noahide laws. By raping Dinah, and

then abducting her, Shechem the son of Hamor committed multiple crimes. As for Shechem’s fellow

villagers, they didn’t utter disapproval, let alone criticize the prince’s felonies. Silence in the face of

crime was tantamount to collusion. According to Noahide standards, Shechem’s fellow citizens’ tacit

consent amounted to culpability – punishable by death.Here's more evidence against the townspeople. Shechem and Hamor gathered their countrymen to

discuss the terms by which Jacob and his sons would dwell among them – they were all to undergo

circumcision. “These men are peaceable with us” the princely father and son declared to the assembled.

“Therefore, let them dwell in the land, and trade therein, for behold the land is large enough for them.

Let us take their daughters for wives, and let us give them our daughters.” The referendum, per se,

passed with loud cheers. And all the men underwent circumcision.Abravanel believes that in the forefront of the men’s minds was one thing: getting their hands on

Jacob’s vast wealth. This, then, is the backdrop to understanding Simeon and Levi’s deadly deed. After

the two killed the villagers, their brothers came and plundered the town.Jacob’s sons taught posterity a lesson in morality, summed up by the sentiment: Fight fire with fire. The

villagers conspired to do harm to Jacob. His sons outsmarted them by taking the initiative. -

Bible Studies: The Story of Judah

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Abravanel observes that chapter 38 digresses from the Bible’s main storyline of Joseph,

training a spotlight on Judah. Why the interlude, Abravanel asks?“And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his

brethren, and turned in to a certain Adullamite, whose name was Hirah.”“And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his brethren”provides key context and

chronology for Judah’s departure. It took place after the brothers sold Joseph into slavery. The majority

of Jacob’s sons were keen to kill Joseph, and had issued a death warrant. Present at the legal hearings,

Judah argued convincingly against capital punishment. As a result, Judah saved Joseph’s life. Selling

Joseph into slavery was the best outcome Judah could manage.Stylistically speaking, the Bible should have followed up chapter 37 – dealing with the sale of Joseph –

with chapter 39, as it pertains to Joseph’s arrival in Egypt. It would read smoothly. Instead, we find

Judah’s story. The interjection comes from left field, per se.Abravanel gleans three lessons, sharing them with Bible students:

1) Historically, Israel has two distinct kingly lines. One gets traced from Joseph through his sons Ephraim and Manasseh. The other hails from Judah, through Perez. Now, Joseph’s sons were born to his Egyptian wife. Hence, that line should not be viewed as legitimate or worthy of the throne. In contrast, Judah’s son’s pedigree ranked, well, royal. It attests to Tamar’s merit and piety, a woman of valor born to righteous Shem, as the Jewish sages taught.

2) The story of Judah highlights his greatness. “And it came to pass at that time, that Judah went down from his brethren…” Judah wanted nothing to do with his cruel brothers who sought to murder Joseph, their innocent brother. Though he eked out an arrangement to spare Joseph’s life, Judah could not reconcile himself with his brothers’ cold-heartedness. Besides, Judah could not bear to see Jacob’s anguish. Abravanel inserts a caveat. Despite Judah’s hard feeling for his brothers, he regularly visited Jacob, showing filial piety.

3) Finally, the story of Judah was written in Scripture for posterity. Bible students, for all time, will see divine providence at work. Here is how. For the ancients, infant and child mortality was commonplace. However, none of Jacob’s children or grandchildren died prematurely, as the Creator kept a vigilant eye over them. The two exceptions were Er and Onan, sons of Judah and his wife Bat Shua. They both died young, as the Bible relates in our chapter: “And Er, Judah’s first born was wicked in the sight of God. And God slew him.”Onan also brought sudden death upon himself: “And the thing which he did was evil in the sight of God. And he slew him also.”

To summarize, Abravanel learns that the story of Judah, though stylistically out of place, imparts

important information that Bible students need to know. -

Bible Studies: The Tower of Babel

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 11, Bible students encounter the inglorious debacle of the Tower of

Babel. Abravanel digs deep into the puzzling storyline. He asks: Where did the generation go wrong?

What underlaid the provocation of the Almighty?“And the whole earth was of one language and of one speech. And it

came to pass, as they journeyed east, that they found a plain in the land

of Shinar. And they dwelt there. And they said one to another: Come, let

us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone

and slime had they for mortar.”Abravanel supplies Bible students with an intriguing, though straightforward, response. Really, he says,

it was a repeat of an earlier and colossal miscalculation that befell Adam, Cain, and their descendants.

We’re talking about a dismal failure to prioritize, to internalize why the Maker made man in the first

place. Abravanel elaborates:God created Adam in His image and likeness. In our context, it means that the Creator fashioned man to

be rational, and acknowledge God in this world. Put differently, man’s raison d’être centers on

perceiving His mighty endeavors. By so doing, man harmonizes and hones his soul.Adam’s task, then, was chiefly a transcendental one. As for God, He provided Adam with a lovely garden,

stocked with abundant, nutritious food and drinking water. Indeed, nature smiled upon Adam and Eve,

and graciously opened its cupboards. First man would not have to lift a finger, let alone toil to live well.

Adam’s only “job” was to recognize his Creator, and live accordingly. Man was meant to live moderately

and enjoy physical pleasures maturely.But Adam missed his cues. A natural life held no appeal. Of creature comforts, he wanted more and

more and more. And so, God expelled Adam from pastoral Eden to a less inviting environment. There, in

humiliation, he would fend for himself in a land cursed by Above.No longer would nature be kind or forthcoming. Adam brought hardship upon himself, all because he

chose to flout the mission that the Maker requested. Backbreaking labor would be his lot. Adam’s son

Cain fared no better. Passion for make-believe amenities derailed him. He farmed an accursed land. Cain

plowed and the soil mocked him; Cain planted seeds and the soil mocked him more. In the end, Cain

resembled a beast of burden, his brow bent over furrows and fields that would yield no more than a

pittance.Abravanel surveys the ill fate of other early man, but for brevity, we omit that part of his discussion and

now turn to the generation who would build the Tower of Babel. Abravanel shows how they, no

differently than their forebears, failed to assume the mantle that God had placed upon them.Understand that God gave sufficient supplies for mankind to subsist. Ample provisions would allow

people to act and live sensibly, while pursuing truth and purpose – nourishing the soul.However, the post-flood generation wanted more. They were not satisfied with a simple and quiet

lifestyle. Instead, they set their sights on building a metropolis, the Tower of Babel its centerpiece.

Urban planners and architects wrote God out of the script. They also rewrote the play book, per se.It became fashionable to buy stuff, acquire things. If it meant stealing from others, well, that presented

no moral problem for people seeking upward mobility. Thievery and murder followed. How different

urban existence compared with agricultural life!Day and night. No longer were folks self-sufficient. For modern society, collectivism stood front and

center. Abravanel quotes King Solomon, who summed it up best: “God made man straight, but they

sought many intrigues.”Though Abravanel writes more, readers get the gist of the point and understand where the generation

of the Tower of Babel went wrong. For the fuller discussion, please seeAbravanel’s World. -

Bible Studies: Yaacov and Esau

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. In Genesis chapter 25, we find a most vexing encounter between Jacob and Esau, twins

born to Isaac and Rebeccah. The story requires context, if Bible students are going to begin to make

sense of it.“And Jacob had been cooking a stew. And Esau came in from the field,

famished. And Esau said to Jacob, Pass this red stew, that I can wolf [it

down], I beg you. I’m famished….And Jacob said, Sell me your birthright

first.”Abravanel provides his interpretation. As is his wont, he hurls poignant questions, in efforts to

understand Jacob’s and Esau’s respective roles within the patriarch’s household. The heated meeting

will do more than define the two brothers’ relationship; it will serve as a primer into western civilization.Certainly, at least taken at face value, the verses quoted above resound with a most unbrotherly tone,

to put it lightly. Abravanel’s questions follow.“And the boys grew, and Esau was a wily trapper, an outdoorsman. And Jacob was a scholarly man who

remained in the tents [of study].”If Jacob was a pure and honest soul, why did he treat Esau, his older

brother, so callously? Why would he strongarm Esau into selling his birthright? And for what – a bowl of

lentils? Let’s be honest. Such conduct is detestable, and certainly not becoming of a man who fears God.

Studious Jacob trained himself to avoid temptation, and that, of course, includes keeping hands off that

which does not belong to him.With regard to Jacob’s ruse to wrest away Esau’s firstborn rights, Abravanel writes more. Readers should

seeAbravanel’s World. But let us share one of Abravanel’s approaches regarding the brothers’

confrontation, one whose aftermath is acutely felt until today.Abravanel believes that Jacob fumed over the brothers’ role reversal, and sought remedy. Let us explain.

Esau and Jacob’s father Isaac had grown old and infirm; he required daily assistance. That meant

someone – the oldest son traditionally – needed to pick up the slack and perform domestic duties.

Chores included procuring food, cooking etc. Moreover, that someone needed to take charge of family

financial affairs.Esau went AWOL and ditched dad. For extended periods of time, he was away from home on hunting

expeditions and other dubious pursuits. Meanwhile, Jacob stepped up. He acted as if he was the family’s

first born, attending to his frail father’s needs.Everything fell on Jacob’s shoulders. Devotedly, he executed all domestic duties – large and small. Thus,

what should have been Esau’s job fell to Jacob – by default. Time elapsed. A pattern emerged. Esau

shunned responsibility. Jacob covered for him.Things came to a head. “And Jacob had been cooking a stew” that day, as he had been countless times

before. “And Esau came in from the field” – after who knows how long. Jacob snapped. Enough of the

charades, the younger brother might have charged. You don’t want to take care of your sick father. I do.

You don’t care about being the first born, and what that entails. I do.Esau merely grunted, “Pass this red stew…I beg you. I’m famished. And Jacob said, Sell me your

birthright first.” For Abravanel, this is crucial context to the brothers’ tense exchange. For Jacob it was a

turning point, a time of reckoning. Esau would either have to change his errant ways or acknowledge the

truth about Jacob’s de facto role in the family.Esau’s predictable answer comes in a later verse, as he scarfs down Jacob’s stew. “And Esau said, Behold

I am at the point to die, and what profit shall the birthright do to me?”In Jacob’s mind, buying the

birthright formalized matters, consistent with the facts on the ground. -

Don Isaac Abravanel: The Garden of Eden’s trees

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508), also spelled Abarbanel was a penetrating Jewish thinker, scholar, and

prolific Biblical commentator. In Genesis Chapter 2, he unearths the meaning of the two trees featured

in the Garden of Eden: the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.Regarding the tree of life, Abravanel questions: How is it that the tree bestows eternal life upon

someone who eats of it? After all, anyone who ingests fruit from any tree can only receive those

qualities or nutrients provided by the tree. Since a fruit’s makeup consists of vitamins and minerals that

remain in man’s bloodstream for a limited time, the impact will be finite. Surely, someone who eats that

fruit does not become immortal.Before Abravanel answers the question concerning the tree of life, he poses a parallel one about the

tree of knowledge of good and evil. It is: How could it be that the tree of knowledge, a tree devoid of

feeling or intelligence, imparts knowledge to the person who eats from it? Again, Abravanel asserts that

fruit can only give to the eater that which itself possesses. So, for example, if pears don’t have any

vitamin k (let alone any emotion or cognition), then a person who eats pears won’t derive any vitamin k

benefit. In our context when we speak about the tree of knowledge, it means that anyone who eats

from that tree shall not receive a boost to his/her I.Q. (intellectual or emotional).Now Abravanel answers the two questions, and we summarize. Abravanel cites the Talmudic sages’

opinion who learn that Adam’s constitution was a sturdy one; he was created to potentially live and not

die. The rabbis’ position concerning man’s super longevity is not inconceivable, writes Abravanel.But Adam sinned when he ate from the tree of knowledge. Disobedience to God’s command abruptly

dashed Man’s death-defying potential. Abravanel believes, that had Adam complied with the Creator’s

request, the tree of life would have facilitated a robust life – earning him eternity.Was Adam originally meant to cheat death and live forever? This question requires explanation. We are

not advocating a position whereby Adam inherently shared traits with the stars and planets, designed to

remain permanent fixtures in the heavens. To be sure, man’s makeup at creation cannot be likened to

the celestials that forever occupy the heavens. That is, Adam was not earmarked to dwell on earth and

not succumb to the grave. Instead, had Adam obeyed God, then the Almighty would have repaid him

handsomely; His kindness and compassion could have catapulted Adam, breathing into him a turbo-

charged existence. But, alas, bumbling Adam blew a golden opportunity to skirt death.Abravanel now turns to discuss the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Let us restate our original

suppositions and definitions. In fact, the fruit held no sway over man’s knowledge base, not of good and

evil in a moral sense (because trees cannot convey morals) and not of I.Q. (because trees cannot convey

intelligence). Rather, Abravanel says that the knowledge fruit worked as an aphrodisiac. The more a

person consumed, the more desirous of sex he or she became.As for redefining the tree of knowledge, Abravanel puts forth that In Biblical parlance, “knowledge”

refers to sexual relations. “Knowledge of good” suggests normal and moderate spousal intimacy;

whereas, “knowledge of evil” conveys exaggerated sexual conduct, lechery.God forbade Adam to eat the intoxicating fruit, as excessive sexual behavior would distract him from

religious values. Crucially, the Torah did not frown upon looking at or even touching fruit from the tree

of knowledge. As stated, Heaven blesses man insofar as he enjoys appropriate spousal intimacy.

However, sexual promiscuity will not be condoned by the One Above. Hence, Adam was told not to eat

the fruit.Genesis chapter 2. Based on Abravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan.

-

Esau’s generations

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. The Bible devotes an entire chapter in Genesis to Esau, meticulously charting out his

family tree. Furthermore, our chapter traces Esau’s move from the Holy Land to Seir.“And Esau dwelt in the mountain land of Seir, Esau is Edom.

Abravanel discusses both subjects, Esau’s descendants as well as his relocation to Seir. See Abravanel’s

World for the fuller treatment of both subjects. For brevity, we will focus on Esau’s generations.

Abravanel questions why the Bible allocates an entire chapter to chronicling Esau’s seed, seeing that The

Five Books of Moses is essentially concerned with the Jewish nation, God’s Chosen People?Jewish attitudes toward Esau are regulated by divine law. “You shall not abhor an Edomite, for he is your

brother.”On a practical level, Abravanel writes, Hebrews need to know Esau’s generations so they do

not infringe divine law by mistreating their brethren. One strain of Esau’s offspring, however, proves the

exception. “And Timna was concubine to Eliphaz, Esau’s son. And she bore to Eliphaz Amalek.” On a

number of occasions in the Bible, we read that the nation of Amalek repeatedly attempted to obliterate

the Children of Israel. God, thus, commanded the Hebrews to be on guard against Amalek attacks,

demanding the Jews to wipe out all memory of Amalek, their nemesis.Abravanel lists more reasons to explain why the Bible records Esau’s generations. Here, we’ll add one

more to the rationale provided above. In the previous chapter, the Bible writes: “Now the sons of Jacob

were twelve.”Each one of Jacob’s twelve tribes was upright. The Maker walked in their midst. How

opposite were Esau’s descendants! The majority of his grandchildren were ill-legitimate, according to

ancient tradition. This is deduced from the verse: “Esau took his wives of the daughters of Canaan, Adah

the daughter of Elon the Hittite, and Oholibamah the daughter of Anah, the daughter of Zibeon the

Hivite.”Tradition attests to Zibeon fathering bastard children with Anah’s wife, who was his daughter in

law.Our chapter testifies to the vast difference in moral character separating Jacob and Esau. While Jacob’s

seed remained chaste and virtuous, the same may not be said about Esau’s descendants; they were

philanderers. The Bible marks that for the record. -

Genesis Chapter 15: Divine Providence

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Genesis chapter 15, Abravanel imparts, is rich in material. He arrives at this conclusion

after considerable study, as he writes. We share a snippet from his intriguing comments, one that is sure

to stand Bible students in good stead. For the fuller discussion, see Abravanel’s World.“After these things the word of God came unto Abram in a vision, saying:

Fear not, Abram. I am your shield. Your reward shall be exceedingly

great.”“After these things, the word of God came unto Abram…” God pays close attention to the affairs of man.

Providence is the interface between the Maker and man. That is a truism when we speak of common

folk. It is especially true when we speak of prophets. In that vein, Abravanel introduces an important

question on chapter 15’s opening verse quoted above: Why did God appear to Avram at this particular

juncture, and what was His message to him?In Chapter 14, we read that Abram had just succeeded in pulling off an extremely impressive military

victory over an army far superior in numbers than his. How did that change Abram’s life? According to

Abravanel, it changed everything!Abravanel theorizes. Before the patriarch handed his royal opponents a drubbing, and prior to Abram

restoring the captives and chattel to the king of Sodom, life for the patriarch was carefree. A picture of

serenity.That changed après la guerre. Anxiety gripped Abram. Gone were halcyon days, when worry and angst

were unknown. Gone were the quiet days and nights, when the patriarch was footloose and carefree.

Abram’s military feat carried concerns of revenge. As Abravanel puts it, noble warriors don’t take

military setbacks lightly. They will retrench and keep a peeled eye open for the right opportunity to

avenge their honor.In practical terms, that meant Abram required around the clock bodyguards – lots of them. The

patriarch understood that his days of working as a farmer were a thing of the past. Thoughts of ruthless

and crafty adversaries preoccupied him.Abram’s sweet and uninterrupted sleep after toiling in the fields was history. In the patriarch’s mind,

nighttime filled with horror, fright. Daytime offered no respite. Wherever Abram turned, he saw sword

toting bodyguards, reminding him of his new reality.It weighed heavy upon the patriarch, especially because he was unused to restraints. Abram felt that his

life hung in the balance. In a flash, battle cries could erupt, fueling further tension.Abram’s angst didn’t stop there. Ever since he returned the chattel to the king of Sodom, he fretted. His

stomach ached to consider what he had done. Was it morally reprehensible to return the loot over to a

king and his countrymen who were evil and rotten to the core, sinners against the Almighty’s values? Far

preferable, Abram questioned, had he kept it for himself. With that money, he could have funded and

fed his soldiers, now patrolling 24/7.In both regards, Providence soothed the patriarch’s sore soul. “Fear not, Abram. I am your shield.” He

heard God’s assuring words. Abram need not think about existential threats from enemies, nor did he

need bodyguards. God had his back.Further, when it came to returning war spoils to the king of Sodom, the Creator let the patriarch know

that he need not second guess himself. Abram’s altruism was apt. “Your reward shall be exceedingly

great.”Heaven would shower blessing and bounty upon the patriarch. He learned that since the King of

Kings would reward him, it would be an affront to accept gifts from mortal kings, even small ones. -

Genesis Chapter 45: Joseph Sends Wagons

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Chapter 45 brings the revelation that Pharaoh’s viceroy is Joseph. Abravanel shares

profound insights that Joseph had gained along his painful journey in reaching the pinnacle of success.

That journey would pave the way for the family’s deep wounds to heal. At the end of the chapter, focus

shifts to Jacob. How will they break the incredible news that Jacob’s beloved son is alive?“And they told him saying, Joseph is yet alive. And he is ruler over all the

land of Egypt. And his heart fainted, for he believed them not. And they

told him all the words of Joseph, which he had said unto them. And

when he saw the wagons which Joseph had sent to carry him, the spirit

of Jacob their father revived. And Israel said, It is enough Joseph my son

is yet alive. I will go and see him before I die.”Abravanel peers into Jacob’s psyche, when his sons return from Egypt and approach him, “saying,

Joseph is yet alive.”From the time of Joseph’s disappearance, Jacob coped with the pain by building a

wall. Whenever Joseph’s name was mentioned, the patriarch withdrew. He checked out.And so it was when Jacob heard, “Joseph is yet alive.” The patriarch’s defense mechanism went up, “And

his heart fainted, for he believed them not.”Twenty-two years of despair erected a barrier that no one

could penetrate. Jacob’s sons had seen their father’s blank stare before. Indeed, they had become all

too familiar with that wan look whenever any association with Joseph passed their lips. Fresh pain

overtook Jacob. It was as if Joseph had died that very day.Jacob would not allow himself to believe for a second, that his precious Joseph was yet alive. Still, his

sons persisted. Talk therapy. “And they told him all the words of Joseph, which he had said unto them.”

The pained patriarch’s soul heard words, scripted by Joseph.Jacob’s disbelief began to slowly melt away. “And when he saw the wagons which Joseph had sent to

carry him, the spirit of Jacob their father revived.” Jacob looked up and saw a royal fleet of wagons that

could only belong to Pharaoh. For once in over two decades, Jacob could lower his defense mechanism.In time, Joseph’s brothers conveyed the story of Joseph’s rise to power in Egypt. “And he is ruler over all

the land of Egypt.”Jacob pined to see Joseph. He wasn’t moved by Joseph’s top position. Nor was Jacob interested in

Joseph’s astounding accomplishments. For twenty-two years, one thing tugged at Jacob, without let up

day in and day out. An image of Joseph’s face had indelibly burrowed itself into his inner being, his heart

and soul. “It is enough Joseph my son is yet alive. I will go and see him before I die.” For the aging

patriarch, an arduous ride down to Egypt would be a breeze, each moment bringing him a step closer to

the fulfilment of his wildest dream. -

Genesis Chapter 47: An Egyptian Famine

Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Roughly half of chapter 47 pertains to Egypt’s economic collapse, as the famine

impoverished an entire population.“And there was no bread in the land…And Joseph gathered up all the

money that was found in the land of Egypt. And Joseph said: Give me

your cattle, and I will give you [bread] for your cattle…So Joseph bought

all the land of Egypt for Pharaoh. And as for the people, he removed

them from city by city…And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt…and they

acquired possessions, and were fruitful and multiplied exceedingly.”Verses ploddingly detail the general and steady decline. Briefly, when the Egyptian’s grain finished, they

spent all their money buying from Pharaoh’s storehouses. Next, there was no money to purchase food.

To forestall starvation, Egyptians sold their livestock to pay for food staples. As the economy further

tanked, Joseph acceded to the people’s offer to barter food for their land, with 80% going to the

farmers, the remaining 20% levied as a government tax.The chapter winds down and teaches us about widespread Egyptian population transfers, before

reaching its conclusion: “And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt…and they acquired possessions, and were

fruitful and multiplied exceedingly.”Abravanel poses a fundamental question: What is this Egyptian story doing in Holy Writ? It is the stuff of

history and belongs in Egyptian annals, but certainly not in the Bible.To the contrary, Abravanel writes. There is a definite Hebrew angle and the Torah conveys four major

takeaways, giving Bible students a glimpse into divine providence, as it relates to the Jews, the Chosen

People.1) It says in Psalms: “Behold the eyes of God are toward them who fear Him, toward them who

wait for His mercy. To deliver their soul from death, and to keep them alive in famine.” While

Egyptians languished, the Hebrews thrived, as per our chapter’s last verse.2) God’s providence shone brightly on His people via Joseph, who funneled money to his family,

catering to their every need. This stands in stark contrast to Egypt, reeling from the mighty

famine. Miraculously, no one badmouthed Joseph for his overt favoritism.

3) The Jews looked on as Egyptians were forcibly moved from one place, far away to another. Few

calamities rank as humiliating as being uprooted, a fate suffered by the local population. As the

saying goes, misery loves company. Displaced Hebrews from Canaan felt a bit of comfort

knowing that they were not the only ones to be shunted from home.4) Pharaoh taxed the Egyptians 20%, in the form of produce. Later, when the Hebrews received the

Law at Sinai, including an obligation to pay tithes to the priestly tribe and to the poor, Jews

would not complain. After all, they had seen the Egyptians pay a hefty levy to their king.In sum, Abravanel shows that this chapter, on the surface, may seem like an Egyptian story, but for the

discerning reader, lessons of faith and divine providence abound.Based on Abravanel’s World of Torah, by Zev Bar Eitan

-

Genesis Chapter 47: Jacob and Sons in Egypt

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. The end of chapter 47 focuses on Jacob’s final days. Earlier in the chapter, we read that

Joseph introduced Pharaoh to Jacob, an encounter the Bible records.“And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt seventeen years, so the days of

Jacob, the years of his life, were a hundred and forty-seven years.”The king beheld an old man who appeared ancient, prompting him to ask the patriarch: “And Pharaoh

said unto Jacob: How many are the days of the years of your life?” To this, Jacob answered that he was

one hundred and thirty years old.Abravanel poses an obvious question. If when Jacob arrived in Egypt the hoary patriarch was one

hundred and thirty, and then we read the verse quoted above, namely, that Jacob lived in Egypt

seventeen years, why does the Bible bother adding the two sums together to arrive at one hundred and

forty-seven? Simple math.Abravanel explains. After Jacob heard that Joseph was alive in Egypt, he thought to travel to see his

precious son there, and return home to Canaan immediately. No dallying. But then, Jacob arrived in

Beer-Sheba, where God appeared to him.The patriarch learned about a change in the schedule. Heaven informed Jacob that he and his family

would spend years in Egypt, and that in Egypt he would eventually die.Jacob learned more. “And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt, in the land of Goshen.” As for Israel’s sons:

“And they acquired possessions therein, and were fruitful, and multiplied exceedingly.”Years of good

and plenty. Finally, the patriarch heard God tell him the Hebrews would remain in Egypt until He

redeemed them. In a word, Jacob was schooled in the facts of life: God runs the show. His timetable.In sum, Jacob had originally surmised that he would visit Joseph and head back home. The Creator had

other plans. “And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt seventeen years.”Concerning Jacob’s family, the

previous verse told of their prodigious success and growth: “And they got them possessions therein, and

were fruitful, and multiplied exceedingly.”The way things turned out, Jacob did not leave Egypt, as he supposed. Instead, he and his family sunk

deep roots in Goshen. When Joseph’s brothers met Pharaoh, they expressed their intent to ride out

Canaan’s famine and immediately go home: “And they said unto Pharaoh: To sojourn in the land are we

come…”Indeed, nothing of the sort transpired. Jacob and family didn’t budge. And it wasn’t because the

patriarch met a sudden death, and didn’t have time to leave. “And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt

seventeen years.” There was ample opportunity – seventeen years to be exact – to return. Says

Abravanel, that is the reason the Bible adds the two numbers (130+17). It conveys that God’s counsel,

and not Jacob’s or his sons’ plans to the contrary, hit the mark. -

Genesis Chapter 48 : Jacob's Final Days

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Chapter 48 brings Bible students closer to Jacob’s final days. The patriarch summoned

Joseph, as our chapter recounts. The blind patriarch revealed to Joseph divine secrets about the future,

a destiny that Heaven laid bare before him in Luz, decades earlier.“And Jacob said unto Joseph: God Almighty appeared unto me at Luz in

the land of Canaan, and blessed me. And said unto me: Behold, I will

make you fruitful…. And I will make of you a company of peoples, and

will give this land to your seed after you for an everlasting possession.

And Israel beheld Joseph’s sons, and said: Who are these? And Joseph

said unto his father: They are my sons, Whom God has given me

here…Now the eyes of Israel were dim for age, so that he could not

see.”Abravanel zeroes in on the father-son dialogue. Jacob, as stated, revealed to Joseph that which the

Creator had foretold in Luz. Mysteries galore. Now, as he lies dying, the hoary patriarch could make out

shadows of two men within earshot, hearing Jacob’s divine secrets. It prompted Jacob to ask: “Who are

these?”Answering, Joseph responded: “They are my sons, Whom God has given me here.”Abravanel asks concerning Joseph’s answer: Why did Joseph tell his father that God had given him two

sons in Egypt? Jacob, of course, knew that when Joseph went to Egypt, he was single and had no

children.Abravanel clarifies what Joseph meant. Jacob realized that his private conversation with Joseph, was,

well, not private. Two others had been present, eliciting the visually-impaired patriarch’s curiosity:

“Who are these?” Joseph had been listening intently, as his father revealed the future, things he had

heard in Luz. “They are my sons, Whom God has given me here,” Joseph replies.Joseph wanted to show Jacob that he understood God’s prescient message, uttered in Luz. “Here” does

not refer to location – Egypt. The fact that Ephraim and Manasseh were not born in Canaan was

abundantly clear. Instead, Joseph conveyed the reason behind his fathering two sons in Egypt. “They are

my sons, Whom God has given me here.” That is, as Joseph processed and internalized what God had

foretold to Jacob in Luz.“And said unto me: Behold, I will make you fruitful…And I will make of you a company of peoples…”

Because of that prophecy spoken in Luz, Joseph comprehended that he had been blessed by Above with

these two sons. Put differently, Joseph realized that elements of the Luz communication materialized. As

a consequence of God’s promise, he had fathered Ephraim and Manasseh in Egypt. -

Genesis Chapter 50: Jacob’s Funeral Procession

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible.Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was a preeminent Jewish thinker, scholar, and prolific Biblical

commentator. Chapter 50 closes out the book of Genesis, chronicling the state funeral procession

accorded to Jacob, the third Hebrew patriarch. Indeed, the procession had been widely attended by

family and Egyptian royalty. “And all the house of Joseph, and his brethren, and his father’s house, only

their little ones and their flocks and herds, they left in the land of Goshen. And there went up with him

both chariots and horsemen. And it was a very great company.”“And when the days of weeping for him were past, Joseph spoke unto

the house of Pharaoh saying: If I have found favor in your eyes, speak, I

pray you, in the ears of Pharaoh saying: My father made me swear,

saying: Behold, I die. In my grave which I have dug for myself in the land

of Canaan, there you shall bury me.”The Bible mentions that the Jews’ children, as well as their flocks and herds, remained back in Egypt.

Abravanel questions why Bible students need to know about the cattle and sheep. Was the livestock

planning on taking part in Jacob’s burial, digging his grave? Were cows and goats to deliver stirring

words of eulogy, Abravanel wryly remarks?Here is the import. Regarding court protocol, Abravanel writes that while Joseph grieved over his father,

he did not permit himself to speak to Pharaoh’s attendants, let alone to Pharaoh himself. This reflects

mourning practices, requiring immediate family of the deceased to rend their garments and put on

sackcloth. It would be an affront to the throne, had Joseph appeared publicly.“Joseph spoke unto the house of Pharaoh”, for Abravanel, is not literal. Rather, it teaches that Joseph

coached his brothers. They appealed to the house of Pharaoh, soliciting them to have Pharaoh grant

permission to bury Jacob in Hebron. “Now therefore let me go up, I pray you, and bury my father. And I

will come [right] back.”Joseph’s family bolstered their petition with an oral promise made by Joseph to

the patriarch: “My father made me swear…”Pharaoh granted leave. He was duly impressed with the solemn oath: “And Pharaoh said: Go up, and

bury your father, as he made you swear.”Great care went into the planning of Jacob’s funeral procession; it would pay homage to the patriarch.

“And Joseph went up to bury his father, and with him went all the servants of Pharaoh, the elders of his

house, and all the elders of the land of Egypt.”Abravanel interjects that Pharaoh may have had ulterior

motives. That is, the monarch may have feared that Joseph and his family might decide to stay in

Canaan, after the interment of their father. It attests to Pharaoh’s observation that Jacob held great

affinity for the Holy Land, while he lived, and even in death. In fact, the twelve tribes hoped to emulate

their father.Pharaoh wouldn’t hear of it. He began eying the Jews as a potential cheap source of labor. The Hebrews

sought to assuage the king’s concerns, assuring him they had no intention of remaining in Canaan. “Only

the little ones and their flocks and herds, they left in the land of Goshen.”Their womenfolk, babies, and

livestock served as surety; they would not abandon their families and wealth.Thus, the Bible describes Jacob’s funeral procession. It included the Hebrews and Egyptian notables.

Notably, not all of the patriarch’s family was allowed out. “Only their little ones and their flocks and

herds, they left in the land of Goshen.”For the Hebrews, a storm was brewing. -

Jacob's Dilemma

Bible studies with Don Isaac Abravanel’s commentary (also spelled Abarbanel) has withstood the test of

time. For over five centuries, Abravanel has delighted – and enlightened – clergy and layman alike,

offering enduring interpretations of the Bible. In Genesis Chapter 46, we read that Jacob packed up his family to leave famine-plagued Canaan

for Egypt, where Joseph ruled. A stopover in Beer Sheba, and a night vision there, nearly put a spike in

the patriarch’s plan. Abravanel puts our verses into perspective. Bible students are the richer for it.“And Israel took his journey with all that he had, and came to Beer-

Sheba, and offered sacrifices unto the God of his father Isaac. And God

said unto Israel in the visions of the night, and said: Jacob, Jacob. And

he said, Here I am. And He said, I am God, the God of your father. Fear

not to go down into Egypt, for I will there make of you a great nation.”Abravanel asks: Why did God need to appear to Jacob in Beer-Sheba in order to calm his concerns? “And

He said….Fear not to go down to Egypt.”Curiously, the patriarch gave no impression of fearfulness. At

the end of the last chapter, Jacob seems to state matter-of-factly: “And Israel said…I will go and see him

before I die.”Our chapter segues from the previous one: “And Israel took his journey with all that he

had, and came to Beer-Sheba…” No worries.Abravanel teaches that Jacob began his journey to Egypt with a stop to Beer-Sheba, because the place

carried warm associations – the patriarchs prayed there. Further, when Jacob fled Canaan for Paddan-

Aram, he had stopped there. That night, Jacob had his ladder vision, a dream that promised him divine

protection.Presently, when Jacob came to Beer-Sheba, he “offered sacrifices unto the God of his father Isaac.”

Abravanel finds it odd that Jacob didn’t mention, and invoke, his grandfather Abraham, referring only to

his father Isaac.Here is Abravanel’s read on the verses. Jacob yearned to visit Egypt and set his eyes upon Joseph. On the

other hand, the patriarch feared leaving the Holy Land, the land that divine providence calls home. Here,

then, was Jacob’s quandary – to go or not to go.This much Jacob knew, as he grappled for clarity. His grandfather, Abraham, had left Canaan for Egypt

during a famine. Yet, after the binding of Isaac, God said to Isaac: “Do not go to Egypt.”The reason for

God’s injunction had to do with wanting to spare Isaac from seedy Egypt, a society immersed in sorcery

and black magic. A mindless culture.Abraham was permitted to go to Egypt, because divine providence had not yet been assigned as a

guiding force to him. But, as a result of circumcision and the binding of Isaac that changed; providence

attached to the first patriarch’s descendants. God had cleaved to the Chosen People, and the Chosen

People – His servants – cleaved to Him. And providence, as stated above, permeated throughout

Canaan.This brings us back to Jacob’s predicament. Isaac was told to remain in the Chosen Land, for God’s eyes

are ever watching over it. Recall, that young Jacob experienced the same uneasiness as he fled the Holy

Land for Paddan-Aram. In the ladder dream, God assured him that He would protect him. “I will be with

you and guard you.” For Jacob’s part, he reciprocated in kind in the form of a pledge. He vowed that

when he returned from Paddan-Aram, he would wholeheartedly serve the Creator.Now, Jacob arrived in Beer-Sheba, in need of divine inspiration. Should the patriarch abort his dream of

seeing Joseph in Egypt? Jacob “offered sacrifice unto the God of his father Isaac.”Would God forbid

Jacob from leaving the Holy Land, as He had stopped Isaac from going there?A deeply-conflicted Jacob so wanted to see Joseph, just for a second. The patriarch poured his heart

before God, praying for a dispensation. The Maker told him: “And He said, I am God, the God of your

father. Fear not to go down into Egypt.”From Above, permission was granted.

Page 2 of 3