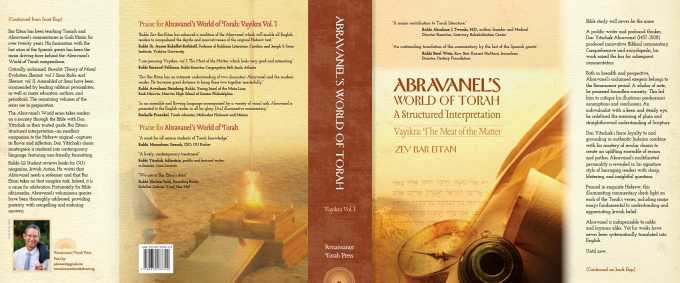

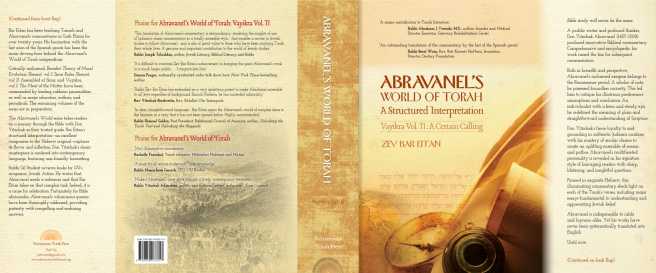

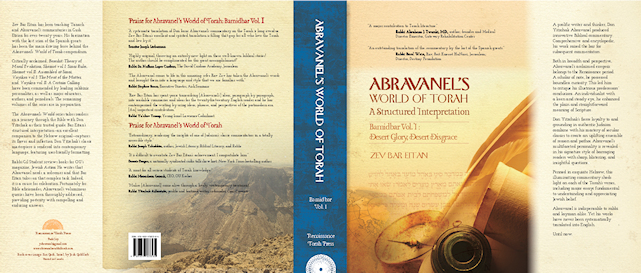

Abravanel’s World of Torah: Series

PRAISE FOR THE WORK

An outstanding translation of the fascinating commentary by the last of the Spanish greats.

Rabbi Berel Wein

A major contribution to Torah literature.

Rabbi Abraham J. Twerski, MD

An interpretive reading in crisp, contemporary English.... [An] important contribution.

Yitzchok Adlerstein

Rabbi; cofounder, Cross Currents

Rabbi Zev Bar Eitan has embarked on a very ambitious project to make Abarbanel accessible to all Jews regardless of background. Baruch Hashem, he has succeeded admirably.

Rav Yitzchak Breitowitz

Rav, Kehillat Ohr Somayach

In clear, straightforward language…Bar Eitan opens the Abravanel’s world of complex ideas to the layman in a way that it has not been opened before. Highly recommended.

Rabbi Shmuel Goldin

Past President, Rabbinical Council of America; author, Unlocking the Torah Text and Unlocking the Haggada

Rabbi Zev Bar-Eitan…has achieved a rendition of the Abravanel which will enable all English readers to comprehend the depths and innovativeness of the original Hebrew text.

Rabbi Dr. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff

Professor of Rabbinic Literature, Caroline and Joseph S. Gruss Institute, Yeshiva University

In an accessible and flowing language accompanied by a variety of visual aids, Abravanel is presented to the English reader in all his glory. [An] illuminative commentary.

Rachelle Fraenkel

Torah educator, Midrashot Nishmat and Matan

A masterful rendition…lucid, free-flowing and interesting.

Rabbi Zev Leff

Rabbi, Moshav Matityahu; Rosh Hayeshiva, Yeshiva Gedola Matityahu

I am perusing Vayikra, Vol. I: The Meat of the Matter, which looks very good and interesting.

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman

Rabbi Emeritus, Congregation Beth Jacob, Atlanta

Riveting and flowing elucidation of the text simplifies complex ideas leaving the reader readily able to grasp the Abravanel’s inner meaning and purposeful explanation.

Rabbi Meyer H. May

Executive Director, Simon Wiesenthal Center and Museums of Tolerance

Open[s] our eyes and minds to the fascinating world of the Abravanel and his unique way of analyzing the Torah...in a user-friendly commentary.

Rabbi Steven Weil

Senior Managing Director, OU

Zev eminently succeeds in making the awesome wisdom of Don Isaac available to the English-speaking public. We are in Bar Eitan’s debt.

Rabbi Sholom Gold

Founding Rabbi, Kehillat Zichron Yosef, Har Nof

The translation is as beautiful as the original Hebrew and the English reader loses nothing in this excellent rendition.

Rabbi Allen Schwartz

Congregation Ohab Zedek, Yeshiva University

Abravanel needs a redeemer…Bar Eitan takes on this complex task.

Rabbi Gil Student

Student Action

At once a work of scholarship and a treat for the imagination.… Bar Eitan’s Abravanel presents Exodus as great literature, as exciting and gripping as any great Russian novel.

Rabbi Daniel Landes

Rosh Hayeshivah, Machon Pardes

Zev Bar Eitan has an intimate understanding of two characters: Abravanel and the modern reader. He traverses great distance to bring these two together masterfully.

Avraham Steinberg

Rabbi, Young Israel of the Main Line; Rosh Mesivta, Mesivta High School of Greater Philadelphia

An uncommon treat.… Rabbi Bar Eitan is to be commended for providing an accessible entree to this timeless masterpiece.

Rabbi N. Daniel Korobkin

Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto Congregation

Relevant and accessible.… Ideal for teachers as well as Yeshiva High School, Ulpana, Yeshiva and Seminary students alike...a wonderful translation... enjoyable reading....

Rachel Weinstein

Tanach Department, Ramaz Upper School, NY

The clear, easy-to-read language and appended notes and illustrations bring the Abravanel to life, for scholars and laymen alike. A great addition to per¬sonal and shul libraries.

Rabbi Yehoshua Weber

Rabbi, Clanton Park Synagogue, Toronto

Of great value to those who have hesitated to tackle this dense, complex work.… Render[s] the Abravanel’s commentary accessible to the modern reader.

Simi Peters

author, Learning to Read Midrash

A gift to the English-speaking audience.… An important “must have” addition to the English Torah library.

Chana Tannenbaum

EdD, lecturer, Bar-Ilan University

The thoughts of a Torah giant over 500 years ago in terminology understand¬able to the modern reader.

Deena Zimmerman

MD, MPH, IBCLC,author; lecturer

Allows the reader the opportunity to see firsthand the brilliance, creativity, and genius of this 15th-century Spanish biblical commentator.

Rabbi Elazar Muskin

Young Israel of Century City, Los Angeles

An excellent job bringing to life the profound ideas of one of the most original thinkers in Judaism and making them relevant and interesting 500 years later.

Rabbi Dr. Alan Kimche

Ner Yisrael Community, London

I really enjoyed the volume on Bereishis. It opened my eyes to the profundity of the Abravanel's commentary and for that I am ever grateful to you. I recommend it to all my students here at the University of Arizona who are searching for an in-depth understanding of the Chumash. Thank you very much for all your efforts. I am excited to read the next volumes on Shemos and Vayikra!

Rabbi Moshe Schonbrun

Senior educator, JAC University of Arizona

I’ve really enjoyed reading Abravanel's World of Torah. Abravanel was a great and original thinker whose perspective has broadened my understanding of Torah. Rabbi Bar Eitan presents Abravanel’s thought clearly and lucidly. I highly recommend his work. I’ve also really benefitted from being able to email Rabbi Bar Eitan regarding points where I needed further clarity.

Alistair Halpern

London

I want to tell you how much I'm absolutely enjoying Abravanel's World: Bereshit. I'm not much of a Torah scholar, but this is wonderful and terrific due to the seamless integration of Abravanel's thought and Bar Eitan's explication. All the kudos in the world. I'm looking forward to you completing the set.

Michael

New Jersey